-

MAP: which areas in France already have water shortages?

Water reserves are above average in some areas due to heavy autumn rainfall but some areas have shortages

-

Vosges birds to ‘recuperate in Norway’ as part of French trial

The plan is aiming to help the emblematic birds, proponents say - but critics say it is a ‘textbook example of what not to do’

-

Book shows how to cook with the weed black bryony in south-west France

‘It’s a local speciality with a taste like nothing else,’ says mayor who published recipe book

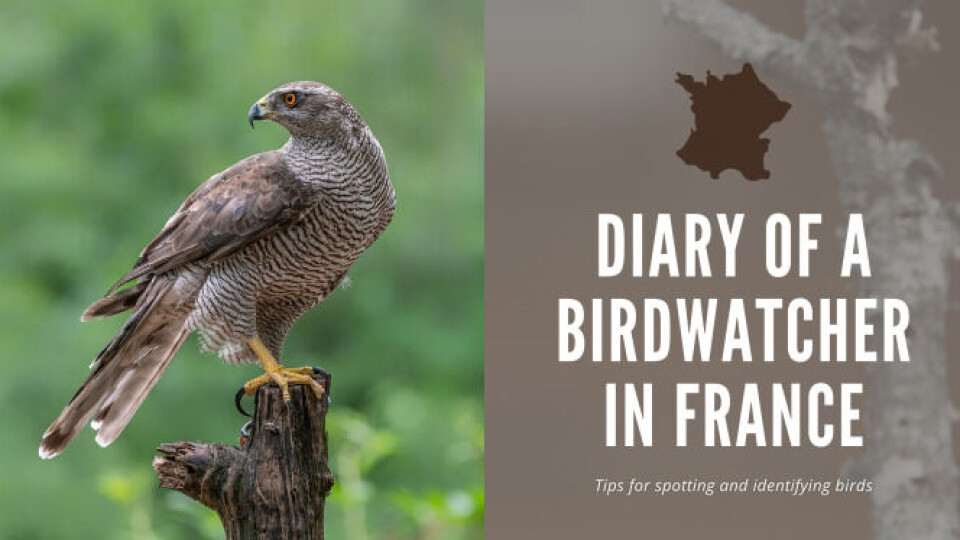

Diary of a birdwatcher in France: Goshawks

Jonathan Kemp describes how his chickens had a recent close encounter with a female goshawk, a large but elusive bird.

I was working in my garden a couple of mornings ago when I suddenly heard a strange sound from one of our chickens, a strangled squawk I had never heard from a chicken’s beak before.

She ran towards me – we treat them like pets and do not have a cock so they are imprinted on us – so I went to look around the back of the garage from where she had come.

Squashed under some roof sheets there was a female goshawk (autour des palombes) trying to grab another chicken, who was hiding amongst some wood offcuts, fortunately just out of reach of her talons. The goshawk also gave a strange sound of fear as it saw me, wriggled itself free of the sheets and sped off through the trees in a flash, leaving one downy feather that must have been torn off in its panic to get away from the hated human.

I knew it was a female because of its size – At a one-metre distance, I could see that it was enormous, unexpectedly so. It was the size of a buzzard, bulky and powerful.

The males are, as in many raptors, about one third smaller, and a male gos can be mistaken for a female Sparrow hawk, but there was no mistaking this magnificent (if terrifying for the chicken) bird.

They have a reputation for ferocity, which Helen Macdonald in her award winning book H is for Hawk somewhat dispels, but the face of a goshawk does not welcome intimacy, with its hard, somewhat manic yellow eyes.

For such a large bird it is surprisingly elusive, hiding as it does in the depths of woodland where it practises its deadly arts of stealth hunting, sliding and slicing through the trees in pursuit of fleeing birds.

Females can take much larger birds than the males; when she has finished her hatching duties she has hungry beaks to feed as well as her own, and can kill and carry something as large as a pheasant (faisan de colchide).

Only in early spring is it possible to see the goshawks; the ‘sky dance’ as the couple swirl and pirouette high in the air, displaying for each other; after that they simply disappear into the dark shadows of woodland. I suspect there will be a nest nearby to the mill, where I live, but I am going to have to be lucky to find it.

Chickens’ other predators in France

It is useful to know what other predators are a threat to the chickens. The list is quite long if you live in the countryside, but urban predators exist also.

One of the best defences is to have a secure henhouse (poulailler) and make sure that it is locked at night.

Check that it is not deteriorating with age, as powerful teeth will chew through weakened wood.

The right dog is pretty dissuasive, especially if it is sleeping outside at night, but it has to be introduced to the chickens so that it knows they are family. Other people’s dogs are a threat - we recently lost two chickens to friends’ dogs, elsewhere chicken-friendly but they did not know ours.

Classically of course, red foxes (renard roux) have always preyed on domestic chickens, and happily live in towns, even if they do so discreetly.

Many years ago when I lived in urban UK, I had chickens, and only found out later that a fox had a den in the garden, but never touched the chickens. Anecdotally, they will avoid hunting too near to their dens, and so avoid reprisal.

The common buzzard, (buse variable) benefits from being a much less feral bird and can well approach human habitations.

It hunts in more open habitat, so if you have an open run it will be a threat. If you see a large raptor perched on a fence post by the road, it is most likely a buzzard. Not to be confused with a golden eagle, which are much larger with a longer tail and different markings.

The mustelid family and wildcats

Then there are members of the mustelid family: The pine marten (martre); the beech marten (fouine); the polecat (putois); and the mink (vison), both European (rare) and the invasive American, often confused with otters (loutres).

There are also wildcats (chat sauvage) and the rarely seen genet (genette).

The pine marten climbs trees, and beside the mink is the most likely to be seen. A sleek cat-sized carnivore that will eat fruit in autumn, its fur varies from light to chocolate brown, with pale ears.

The white patches on the throat vary, so help with identification. Its cousin, the beech marten, is slightly smaller with rounded ears and a peach-coloured nose and lives in more open habitat.

The polecat is known by its white muzzle and variable fur colour, unlike the mink. The domesticated versions are called ferrets.

Mink, especially the American, menace not only domestic fowl but also wild birds and animals such as water voles. Escapees from fur farms have thrived, they are not shy, and very destructive if they invade a henhouse.

If you see a dark-furred animal swimming high in the water about 40 centimetres long with short ears, it is most probably a mink. Take a photo and show it to someone knowledgeable who will probably disappoint your hopes that it was an otter.

The otter has made a come-back in France after years of polluted rivers. A large aquatic animal, much of its diet is fish. It swims low in the water, and can dive to disappear for long periods. Mostly detected by the droppings (fientes) placed on prominent rocks and under bridges as territorial marking.

The lovely animal below is the genet of the viverrid family, introduced from Africa over a 1000 years ago. Only after dark is there a small chance of seeing them.

Identification of the wildcat is problematic as a result of hybridisation with feral and domestic cats.

They are considerably larger and bulkier than feral and domestic cats and have dark rings on their rounded tail, and a dark dorsal stripe that stops at the tail. Ultimately, only DNA analysis can give definitive identification. Again, they are difficult to spot as they hunt at night.

Related Articles

Griffon vultures no longer in danger of extinction in France

Diary of a birdwatcher in France: Vultures

Diary of a birdwatcher in France: The Eurasian woodcock

Diary of a birdwatcher in France: The Eurasian jay

Diary of a birdwatcher in France: Swifts