-

The five other capitals of France before Paris

Several other cities have held the honour for various reasons

-

Duck Cold! Four French phrases to use when it is freezing outside

We remind you of French expressions to use to describe the drop in temperature

-

When and why do we say le moral dans les chaussettes?

We explore this useful expression that describes low spirits

Violette Szabo: British spy who fought Nazis to avenge French husband

She fearlessly worked as a special agent during World War Two, and is remembered today as a war hero in both the UK and France

Violette Szabo was a secret service agent who worked with the Resistance in France during the World War Two until she was captured and killed by Nazis forces.

Her British father, Charles Bushell, had met her mother, Reine Leroy, while serving in France during the war, and Violette was born in Paris. She grew up in London and Picardy, becoming completely bilingual and sounding native in both languages. She was a tomboy, preferring gymnastics, cycling, ice-skating and shooting to needlework. By the time war started, she was a shop assistant, but in 1940 she became a land girl and then worked in a munitions factory.

She met her French husband, Etienne Szabo, at the Bastille Day parade in 1940, and married him just weeks later after a whirlwind romance. She was 19 and he was 31. They had a one-week honeymoon before he left to fight in Senegal, South Africa, Eritrea and Syria. Left alone in London, Violette worked as a switchboard operator during the Blitz, although she found the work boring. Etienne came home briefly on leave in 1941, but was soon sent back to North Africa.

Wanting a more active role in the war, Violette enlisted in the ATS and was trained to operate an anti-aircraft battery, but in early 1942 when she discovered she was pregnant, she was obliged to return to London where she took a flat in Notting Hill. Her daughter Tania was born in June 1942, and tragically that October Etienne was killed in action having never seen his daughter.

Longing to avenge his death, Violette joined the French section of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and began training to become a field agent. She learned field-craft, night and day navigation, weapons, demolition, escape, evasion, uniform recognition, communications and cryptology. She also learned to make parachute jumps.

Fully aware of the dangers she faced, she drew up her will before leaving the UK on her first mission, and on April 5th 1944 was parachuted into Occupied France. She landed near Cherbourg with the aim of assessing how much of the resistance network code named ‘Salesman’ remained after a devastating series of arrests.

She travelled to Dieppe and Rouen to gather intelligence and reconnoitre, discovering that ‘Salesman’ had been almost completely smashed. She also gathered intelligence on which factories were producing war materials for the Germans, which was subsequently used to plot bombing raids.

She flew back to the UK on April 30th, narrowly escaping injury when the plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire leaving France. After more training on June 8th 1944 she went back to France on a second mission, landing by parachute near Sussac, on the outskirts of Limoges. She was part of a 4-strong team tasked with operating a network called ‘Salesman II’. Her job was to co-ordinate local efforts to sabotage German communication lines, but it was decided that she would be more useful acting as liaison officer for the Maquis of Corrèze and Dordogne.

French people were banned from driving cars after D-Day, but despite this a local agent, Jacques Dufour, insisted on driving her half-way there.

Fully realising the danger, Violette requested to be armed with a Sten gun and eight magazines of ammunition. They were accompanied by another resistance member, Jean Bariaud.

In Salon-la-Tour they ran into a German roadblock, and knowing that they would be discovered, they all jumped out of the car and ran for it. Violette twisted her dodgy ankle, weakened from an old parachuting injury, and Jacques Dufour tried to help her but she insisted that he leave her behind.

The story goes that, sheltering behind the trunk of an apple tree, she managed to keep the Germans at bay for half an hour while he escaped. She was captured when her ammunition ran out. The exact truth of events is disputed, but it is certain that she was arrested and taken to Limoges where she was held and interrogated by the SS.

She was then moved to Fresnes Prison in Paris where she was interrogated and tortured by the Gestapo.

On August 8th, 1944, along with some other high-value prisoners, she was transferred to Germany by train, shackled by the ankle to another SOE agent, Denise Bloch, for the entire journey. After a long journey via various other internment camps and prisons, on August 25th they finally arrived at Ravensbrück concentration camp, where more than 92,000 people were exterminated during the course of World War Two.

Despite the terrible conditions, she is reputed to have remained cheerful and kept other prisoners’ morale up with her cheeky Cockney accent. She was only 5’4” tall but her energy and courage along with her constant plans to escape are said to have inspired those around her. She was one of a group of women who refused to make munitions, instead being sent to dig up potatoes.

The group were transferred to Königsberg punishment camp in late October where they worked felling trees, clearing land for an airfield and digging a trench for a light railway, all by hand.

Every morning the women had to stand for roll-call which could last for up to five hours, wearing the summer clothes in which they had been arrested. They had no outdoor clothes, no blankets and precious little food. Many of them simply froze to death.

In January, Violette and two other British agents were sent back to Ravensbrück, where they were beaten and held in solitary confinement. Sometime around February 5th, 1945, all three were finally taken outside and shot. It was recorded that Violette was kneeling. The other two could not walk so were carried out on stretchers to be shot. Their bodies were cremated.

After the war, Szabo was posthumously awarded the George Cross, and in 1947 France awarded both Violette and Etienne Szabo the ‘Croix de Guerre avec Etoile de Bronze’ and she received the Médaille de la Résistance in 1973. Her medals are on display at the Imperial War Museum in London. Her name also features on the SOE War Memorial in Valençay, where a commemoration service is held every year on May 6th.

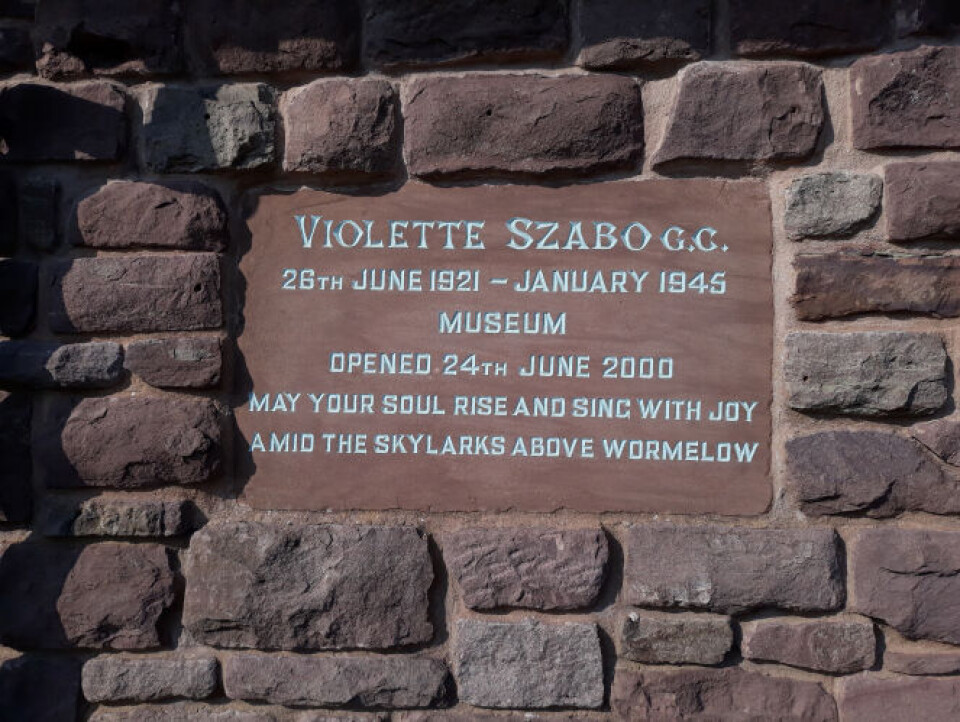

In the UK, the Violette Szabo GC Museum in Herefordshire occupies a cottage formerly owned by Violette’s cousins. Celebration of the centenary of Violette’s birth was held there in 2021.

As an adult, Violette’s daughter Tania, wrote a biography concentrating on her mother’s experiences in France. The book is called Young Brave and Beautiful: The Missions of Special Operations Executive Lieutenant Violette Szabo. Her life was also the subject of R.J. Minney’s book, Carve Her Name with Pride (1956), which was made into a film – of the same name – two years later starring Virginia McKenna and Paul Scofield.

Susan Ottaway’s book, Violette Szabo: The Life that I Have came out in 2001 and her code poem, The Life that I Have has also been published.

A blue plaque was put up at Violette’s family home in Stockwell, and her name is on the memorial plaque at Ravensbrück, the Brookwood Memorial in Surrey and the FANY (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry) memorial in Knightsbridge, London. In 2009, she became the face of the SOE memorial on the Albert Embankment, London.

At least 41 female SOE agents served in Section F (France). Out of them, only 25 survived. Twelve were executed by the Germans, one died in a shipwreck, two died of disease while in prison, and one died of natural causes. They were aged from 20 to 53 years old and although a few of them remained in place for more than two years, most only saw active service for a few months.

Beryl E Escott’s book, ‘Mission Improbable, A Salute to the Royal Air Force Women of Special Operations Executive in Wartime France’ is a collection of biographies of some of these heroines. But many others faded out of the limelight after the war, their courage and daring being in some cases, almost completely forgotten.

Related stories:

Black US D-Day veteran awarded France’s highest honour aged 100

From poverty to glory: Life of legendary French singer Edith Piaf

When naming places and streets, France should honour women too