-

Bergerac airport injects €30million a year into Dordogne

Holidays and weddings in the region accounted for much of the tourism

-

Profile: French supermarket boss Michel-Edouard Leclerc

Modern-day Robin Hood or merciless manipulator of the market?

-

'I helped restore French cathedrals as a female American stone cutter - despite prejudice'

Stella Cheng, who worked on the restoration of Notre-Dame Cathedral, faced sexism and racism

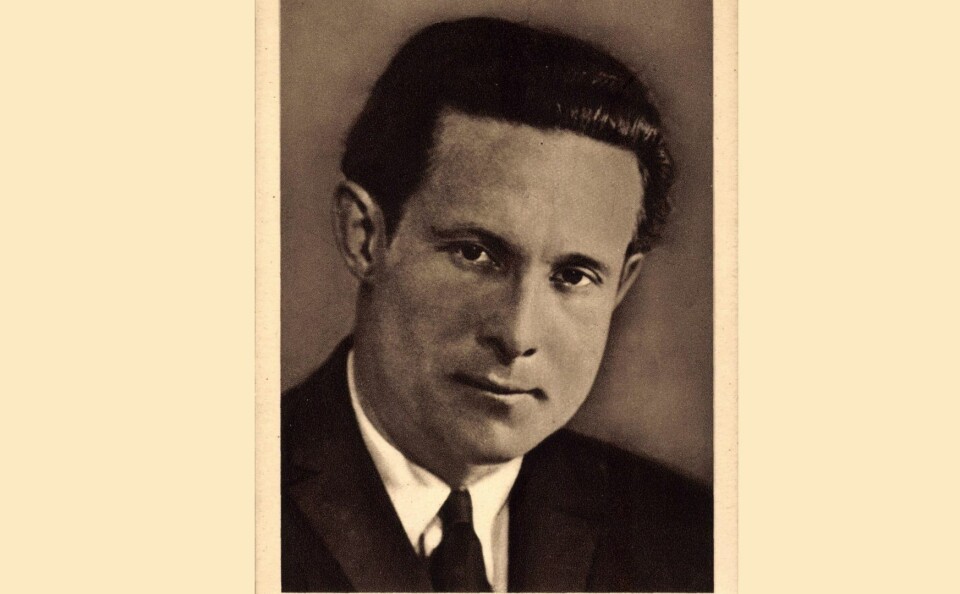

Profile: the daredevil French aviator who started a political party

We reveal the highs and lows of Jean Mermoz, the charismatic pilot who lived his short life to the full

Jean Mermoz (1901-1936) was a pioneering French aviator who also co-founded the French Social Party.

Born in Aubenton (Aisne), he spent much of his childhood with his grandparents.

When WW1 broke out, they fled south to Aurillac (Cantal), taking the boy with them.

Mermoz did not see his mother as she was stuck in the occupied zone until 1917, when she escaped via Switzerland. She then took him to Paris and enrolled him in the Lycée Voltaire.

Read more: Poppy Lady of France recognised with a new biography in English

Learning to fly and crash

In 1920, at the age of 19, he enrolled in the army and ticked the box marked ‘aviation’ on the advice of a friend of his mother’s.

Mermoz learned to fly at the Istres Military School although his talent was not immediately apparent.

He was disgusted how recruits were abused to deter them from flying and when the engine of his plane stalled on take-off, and he crashed into a tree, breaking his leg and his jaw. Another attempt resulted in a crash landing.

He finally passed his test in 1921 and acquired the rank of corporal.

Flew perilous missions in Franco-Syrian War

Assigned to the 7th squadron of the 11th bombing regiment of Metz-Frescaty, he was sent to Syria and Beirut and earned a reputation for volunteering for the most perilous missions.

The Franco-Syrian War of 1920 was fought between France and the Hashemite rulers of the newly established Arab Kingdom of Syria.

The struggle was part of the division of territory that had been the Ottoman Empire, and the French won. They ruled Syria until 1941.

The last French soldier left Syria on 17 April 1946, and the date is still commemorated annually with Evacuation Day celebrations.

Read more: Two remarkable pilots whose lives both took flight in France

Desert crash landing was nearly the end

In 1920, the machines flown by military pilots were badly maintained and unreliable. The technology was in its infancy and even aerodynamics was a nascent field of study.

Engine problems meant that Jean Mermoz broke down repeatedly in the desert.

On one occasion, he and a mechanic spent several days walking after a crash, and were only rescued at the 11th hour, dehydrated and on the verge of collapse.

By 1922, he had logged 600 flying hours in just 18 months.

Medals, malaria and washing cars

By the time he returned to France in 1923, he had been awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Levant Medal – and contracted malaria.

He was off sick for many months before he was fit enough to join a new unit in June. He was finally demobilised in 1924, having made lifelong friends with many of the other pilots.

He remained in reserve, however, and in 1930, he was sent to Toulouse as a reservist officer.

His exploits in the Middle East had already earned him a name as a hero and as a top pilot, but outside the armed forces there were no jobs for pilots.

He worked as a sweeper, a night guardian, a labourer, a car washer, and a scribe addressing envelopes for mass mailouts.

He did a day’s work as a stunt pilot for a film, but apart from that, he did not fly at all.

Reprimanded for flying aerobatics

He was saved from his situation in September 1924 by a proposition from Didier Daurat, the director of Lignes Latécoère, a brand new airmail service between Toulouse and France’s overseas territories.

Read more: Magnificent men – and women – in their flying machines

He started work for them as a mechanic, and then flew a check ride in order to work as a pilot, but was severely reprimanded for flying aerobatics instead of the circuits demanded.

“I don’t need circus artists, but bus drivers,” said Daurat.

Nevertheless he got the job and began flying over the Pyrenees between Toulouse and Barcelona, a challenging route for the planes of the period.

In 1925, he began flying the Toulouse-Malaga route.

More desert crashes threatened his health

Passing through Paris one day, he ran into an old pilot friend, Henri Guillaumet, and persuaded him to apply for a job at Latécoère, too.

In 1926, he began flying Casablanca (Morocco)-Dakar (Senegal), and after an engine failure, made a forced landing in the desert.

He and his interpreter, taking the water from the radiator with them, attempted to walk to Cap Juby in a sandstorm, but were eventually captured by locals who ransomed them back to France.

Signed off sick from the effects of this misadventure, with severe sinusitis, an ear infection and a stomach ulcer, he was terrified he might go deaf and be permanently grounded, but in the event he was back at work two months later, when almost the same thing happened again.

Forced by engine failure to land in the desert, this time, however, he was rescued by a fellow Latécoère pilot, Eloi Ville.

In October 1926, he met Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who had just become the director at Cap Juby, and in an ironic twist of fate, he rescued Eloi Ville from the desert after a forced landing.

The following year, 1927, he and three other pilots went on an expedition to rescue a hydroplane piloted by the Larre-Borges brothers.

Challenge of flying over the Andes

In 1927, Jean Mermoz and another pilot called Elisée Négrin achieved a non-stop flight from Toulouse to Saint-Louis in Senegal, on the same day that another crew managed to reach Dakar in 23 hours and 30 minutes.

By 1927, Latécoère had become the Compagnie Générale Aéropostale (often just called l’Aéropostale, and Jean Mermoz was sent to Rio de Janeiro to develop new airmail lines in South America. They developed the night flights made so famous by Saint-Exupéry, and faced the challenge of flying over the Andes.

The usual mechanical problems were exacerbated by the difficulties of mountain flying, and at one point he was obliged to spend three days repairing his crashed aircraft before attempting a perilous venture that involved taking off and then bouncing the plane off two other, lower plateaus.

They managed, but a radiator hose then came loose and so they had to glide the plane down to Copiapo.

Heartbreaker gets married

Needless to say, the tall, handsome, devil-may-care aviator was a ladies’ favourite. He partied as hard as he flew, and broke many hearts along the way.

In 1929, in Buenos Aries, he met Gilberte Chazottes, and within a few months he had proposed to her. In 1930, when he returned to Paris, Gilberte and her family followed in order to prepare for a June wedding in Paris.

Jean Mermoz, meanwhile, was busy proving that hydroplanes could service an airmail line between Europe and South America.

In July 1930, he crashed into the South Atlantic, from which both he and the airmail had to be rescued.

He finally married Gilberte in August 1930, and a few weeks later had yet another spectacular accident.

A plane he was test-flying went into an uncontrollable spin.

When he attempted to bail out, he realised the hatch was too small for his shoulders. It was only because the machine disintegrated around him that he was finally able to free himself to release his parachute.

Clash with Minister for Transport triggered interest in politics

He continued testing planes, searching for an aircraft capable of flying from Paris to Santiago in Chile. He flew the Marseille-Algiers line himself, beating the world’s distance record, and in 1933, flew from Paris direct to Buenos Aires.

The French government insisted that only hydroplanes could be used to cross the oceans, but he lobbied for lighter, faster ground planes to be used.

Coming into conflict with the new Minister for Transport, he became interested in politics and co-founded the French Social Party.

Having flown across the Atlantic and back with aviator Maryse Bastié, in 1935, he supported her flying school Maryse Bastié Aviation in Orly.

He flew the Atlantic 23 times in his short career, on a diverse range of different planes.

After 8,200 flying hours, Jean Mermoz had disappeared forever

He disappeared in December 1936, along with his co-pilot, navigator, radio operator and mechanic during a flight back from Dakar in a hydroplane.

He had already abandoned the flight once because of a problem with the propeller, but only waited for cursory repairs to be made before taking off again.

Over the radio the crew sent the message “have cut right engine” and the coordinates. Nothing more.

Rescue parties rushed to the spot but the wreck has never been found.

The accident was a tragedy, and his loss was mourned nationally. Even people who had never seen a plane were devastated.

After 8,200 flying hours, Jean Mermoz had disappeared forever.

But Mermoz had established commercial trans-Atlantic aviation, and the world has never looked back.

You can learn more about Jean Mermoz at the Musée Jean-Mermoz in Aubenton (entry from €3), and the Envol des Pionniers museum in Toulouse (entry from €8).

Related articles

French microlight pilot realises her dream to fly solo across Africa

The female French spy who saved more than a thousand British soldiers