-

Where to find good Indian food and curry ingredients in rural France

Connexion readers share their tips on finding spices that hit the spot

-

Ski helmets should be compulsory in France

Two readers share their views on risk and danger on the slopes

-

We went to a French curry house but it didn't hit the spot

Columnist Samantha David laments the lack of decent meals in the style of the subcontinent

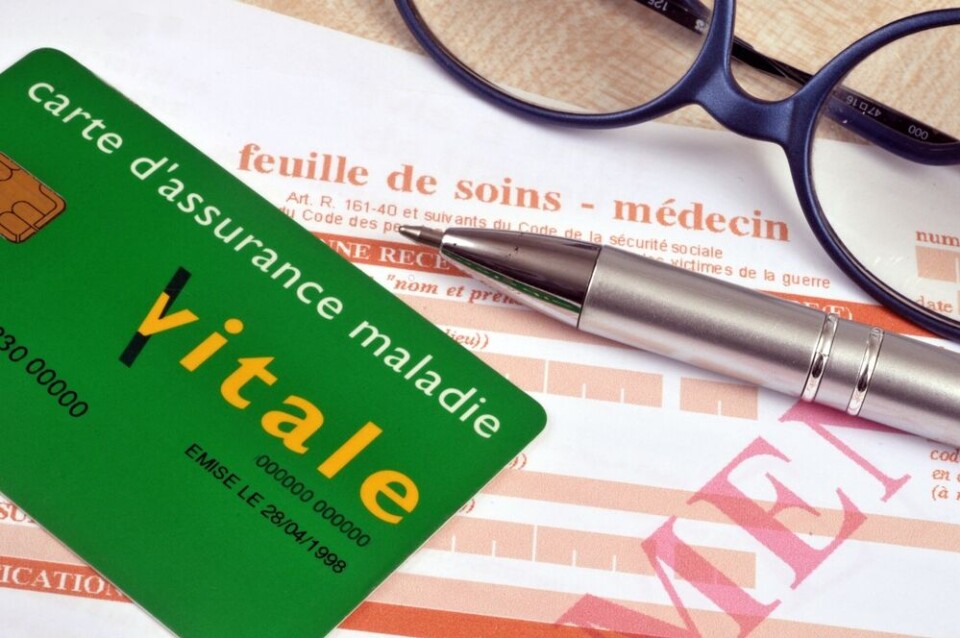

Covid changed my mind about French healthcare: it is exceptional

Writer Tamara Thiessen says the system is not perfect but has many good points. She also notes the chaos of testing facilities she experienced in her native Australia

If you had asked me early in the Covid crisis what I thought of France’s health system, I might have had a different outlook.

I was battling with chronic pain and my so-called médecin traitant (regular GP) was almost impossible to see.

Even when I left her surgery to go and have this or that test, she refused to let me book my next appointment immediately. Instead, I had to wait a month each time.

So my mysterious and debilitating pains dragged on for months – something many of my French friends found inexcusable.

On top of that, when I did finally get an appointment, I found myself in a crammed waiting room of sniffling patients, with no space to sit, for two hours as she saw to people turning up sans rendez-vous.

I changed doctors. That went so-so. I had to wait over an hour for my appointment, “but you will not find a better doctor”, the others told me.

I am not sure about that. Many Americans and Brits love the French healthcare system but there are signs it is going downhill in certain areas, especially with accessibility to a good GP.

I ended up with a misogynistic Samu emergency services doctor, who visited me at home and said all the pain was in my head. The receptionist was equally hostile with a put-down French manner.

Clearly, there are shortcomings in an otherwise adulated system.

First, a shortage of doctors, not only in rural areas but also in parts of Paris and some other big cities, means six to eight million French people (about 10% of the population) reportedly live in a ‘medical desert’ with poor access to healthcare.

We can expect this issue to be at the heart of debates leading up to the presidential election.

In the first wave of Covid, I yearned to be on the other side of the Atlantic, if only for people’s adherence to the rules – in the doctor’s surgery, at least.

However, as the crisis progressed, it was hard to fault the French response, with the smooth vaccination roll-out, beginning in December 2020, well-run public vaccination centres and widely available free tests.

What is more, readily available public information meant fake news from anti-vaxxers had less of a grip on the public than in the US. The accessibility of official facts and figures made it easy for a reporter to help extinguish misinformation. I booked in for my first vaccination in the town hall of Paris’s 15th arrondissement last May and was able to gaze at the splendid frescos on the ceiling during the one-hour wait.

Not so shabby: the vaccination centre in Paris’s 15th arrondissement was located in its historic mairie building. Pic: Tamara Thiessen / supplied by author

Meanwhile, I was watching in horror at Australia’s vaccination fail (I am Australian) – the roll-out did not kick off for months after and, like the testing, was a debacle from the outset.

In Europe, amid the surge in Covid infections over Christmas and the New Year, both Italy and the UK hit problems. But not France. Barely. The predicted shortage of tests never really came to fruition.

In December, I strolled among the walk-in testing tents on the Champs-Elysées then booked a pre-flight test with ease at a laboratory. The results came back within hours.

Free tests were available at thousands of laboratories around France.

In the US, meanwhile, it was a nightmare with people struggling to get tested prior to travel. One friend in America paid $200 on her second attempt at a test (after failing the first time) ahead of a return flight to Paris. Another had to drive 120km to pay much the same.

In Sydney I witnessed the testing shambles first hand. After waiting an hour in a queue at one of only a handful of testing sites, I was turned away. Thousands of Australians’ long-held holiday hopes were thrown into turmoil. Australia sure had the rules – but not the infrastructure.

Back in France a friend walked in for a rapid antigen test over Christmas – and was the only customer at the Strasbourg pharmacy. It is all the more remarkable considering the pressure on the French system in terms of case numbers and its far greater population.

The way it has handled up to half a million Covid cases a day points to how spectacularly good the system is.

Some commentators in Australia put the disaster there down to a lack of investment in public health. In France it seems to be a high priority. Certainly, compared to my (other) homeland, French healthcare is highly affordable, and in that sense fair.

Despite claims – and evidence – of a certain slide in quality, it still shines for most, particularly after the lessons of the past couple of years.

Nancy Niequist Schoon, who lives with her partner between the US and France, said: “It is free to all in France.

“From an airlift off a mountain to an eye emergency on a Sunday at the height of the pandemic, I find French healthcare and caregivers excellent.

“The price-to-care ratio is fantastic. Home visits for follow-up, routine lab visits and X-rays... prices, even without insurance, are a fraction of what they would be in the US. Depending on where you live in the US, healthcare is excellent, but it comes at such a cost.”

Angélique, an American in France for 37 years, does not feel she is seeing the system through rose-tinted glasses.

“We are extremely lucky. Here we have 70-100% medical cover, depending if you have complementary health insurance. The social benefits are incomparable.”

The carte Vitale is an entry ticket to one of the fairest health systems in the world, entitling everyone to cheap public health insurance. Totally free medical cover (complémentaire santé solidaire) is given to low-income households, among others.

One downside is the bureaucracy, which can be a big hurdle.

Foreigners wait anything from three months to over a year to get a carte Vitale and full access to French public healthcare.

“There is a bit of paperwork to wade through each time,” said Ms Niequist Schoon. “Then again, bureaucracy is a French word.”

But even the paperwork has not been terrible this time.

Throughout the pandemic, the state healthcare website Ameli has informed people of their rights and has helped people convert their vaccination records to an EU digital Covid certificate. All this has facilitated travel, and life in general.

Meanwhile, my Facebook page has been swamped with friends’ horror stories about acquiring pre-travel tests and accessing documents online.

Travelling in Europe, I simply have to ask for a carte européenne d’assurance maladie beforehand, and I can travel carefree.

Yes, French healthcare might well be the best in the world after all.

Related stories:

Warning over new scam on French carte Vitale healthcare cards

France Covid: Children of dead health workers made wards of the state

French health insurance data leak: what to do if you are affected