-

The five other capitals of France before Paris

Several other cities have held the honour for various reasons

-

Duck Cold! Four French phrases to use when it is freezing outside

We remind you of French expressions to use to describe the drop in temperature

-

When and why do we say le moral dans les chaussettes?

We explore this useful expression that describes low spirits

How French medieval craftsmen made the stained glass windows of Troyes

Art historian Dr Julia Faiers discovers the colourful secrets and stories depicted in the churches of Aube’s capital city

From small beginnings as a Gallo-Roman town called Augustobona in the first century, the city of Troyes enjoyed a boom period in the Middle Ages.

The town expanded rapidly in the 12th century, gaining new urban districts and, of course, churches to serve the spiritual needs of the burgeoning population.

Troyes’ 12th-century expansion coincided with the emergence of Gothic architecture, a style developed by Abbot Suger in the abbey of Saint-Denis near Paris.

The pioneering work at Saint-Denis transformed church building over the subsequent centuries, allowing for much larger windows than was previously possible. And with this, the art of painting pictures and telling stories in glass took off in churches all over Christendom.

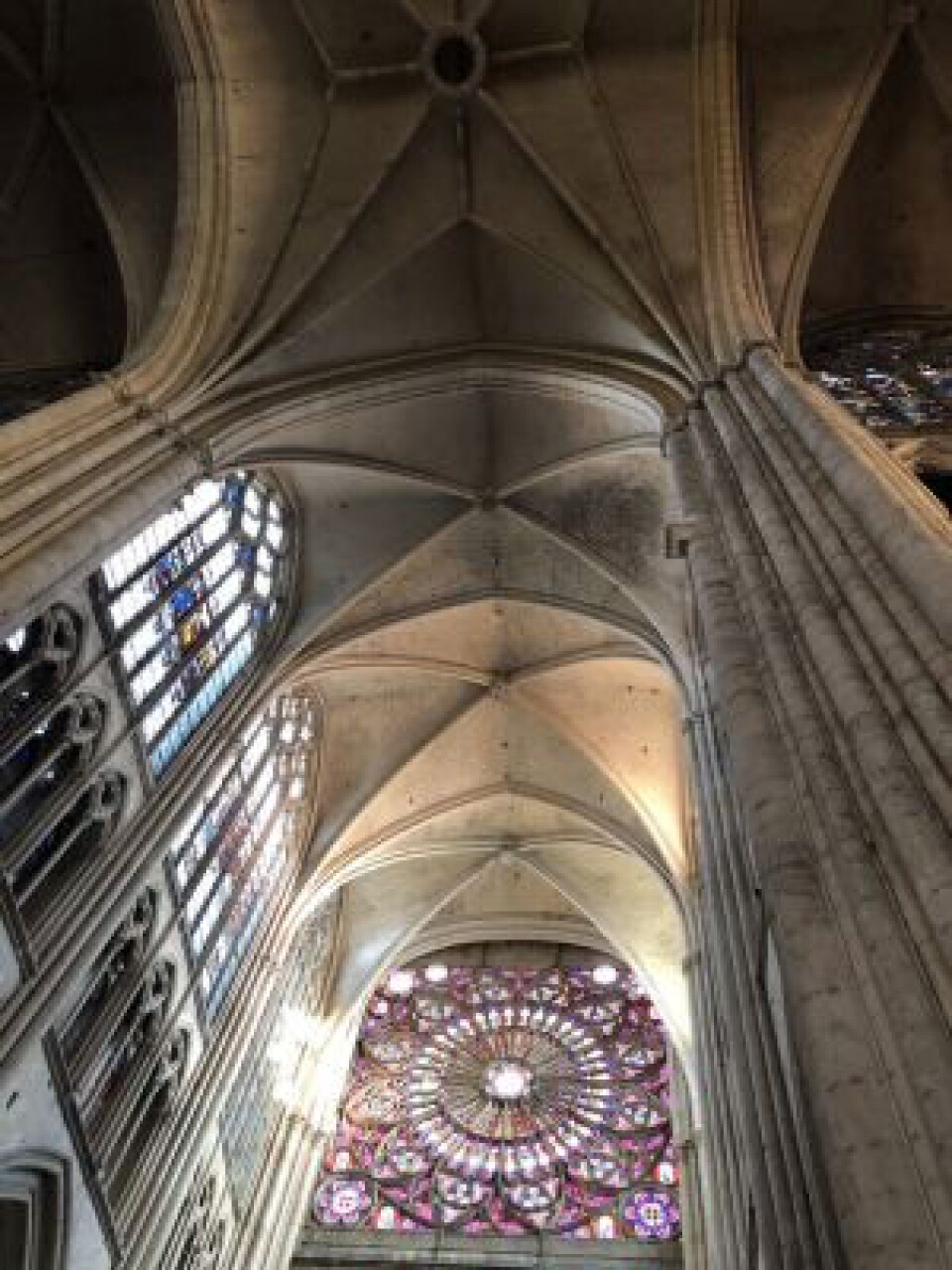

Image: The spectacular rose window in the south transept of Troyes cathedral, a 19th-century copy of the 15th-century north transept rose window; Credit: Dr Julia Faiers

Troyes became a centre for glass making

In the medieval period, the majority of people were illiterate, yet they could see and understand the rich complexity and drama of the Christian message in the windows of their local church.

As well as suffusing sacred spaces with ‘divine’ coloured light, stained-glass windows provided a theological and spiritual education not only for the townspeople in the congregation, but for the clergy who celebrated mass there.

Although Troyes suffered during the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), prosperity returned towards the end of the 15th century, fuelling renovation programmes in the city’s cathedral and parish churches.

Troyes became widely known during this period as a centre for glass making.

Read more: Are modern underpants really shown in medieval French church window?

16th-century windows recount the story of the True Cross

At the cathedral of Saint-Pierre-et-Saint Paul, the church of Sainte-Madeleine, the church of Saint-Pantaléon, and the basilica of Saint-Urbain, the whole of the Christian story plays out in the windows made by the town’s workshops in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Richly coloured windows from the 13th century illuminate the east end of the cathedral, representing popes and emperors, and telling the story of the Life of the Virgin.

In the nave, however, the luminous storytelling in glass reaches another level.

Here, 16th-century windows recount the story of the True Cross, of Saint Sebastian (who was tied to a tree stump and pierced by countless arrows), and a magnificent vision of the Tree of Jesse made at the very end of the 15th century.

This window describes in fascinating detail the genealogy of Christ; from a tree that grows directly from Jesse’s body spring branches bearing the figures of 27 descendants of Jesse.

Image: A close-up of Jesse in the Tree of Jesse window in the church of Sainte-Madeleine. The base of a tree grows from the stomach of Jesse, the father of David, first king of Israel, with each branch showing the ancestors of Jesus; Credit: Dr Julia Faiers

Visceral drama of the famous Mystical Wine Press window

Nearly 125 years later, one of the last glass painters of the Troyes’ workshops, Linard Gontier, produced the now famous Mystical Wine Press window in 1625.

Here, from the body of Christ, shown lying beneath a wine press, sprouts a vine with many branches – a vivid illustration in glass of a verse from the Gospel of St John, in which Christ proclaimed “I am the vine, you are the branches.”

And to add to the visceral drama, the blood squeezed from his body by the wine press is collected in a chalice in the foreground at the bottom of the window, where it can easily be seen by the congregation.

Read more: Paris chapel named one of best hidden secrets in tourist poll

Each window panel tells a separate story in glass

A 15-minute walk from the cathedral to the church of Sainte-Madeleine rewards the visitor with more spectacular stained glass.

The oldest church in Troyes, built in the 12th century, had a major facelift in the 16th century, including new windows around the chevet (the area at the east end).

Look out for another rendition of the Tree of Jesse, and to the right of the apse, the richly detailed window that tells the story of Christ’s Passion.

Each panel tells a separate story, including the Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, the Kiss of Judas, and the Last Supper.

Image: A close up of the Passion window in Sainte-Madeleine, showing the bottom right panes with the kneeling donors Catherine Boucherat and her daughters; Credit: Dr Julia Faiers

And in the prime spot at the bottom of the window, portraits of the donors remind worshippers of their generosity and piety.

And if you want to enjoy stained glass outside of Troyes’ churches, visit the recently refurbished Cité du Vitrail museum (City of Stained Glass), which tells the story of stained glass from the 12th century all the way up to the present.

How did medieval craftsmen make stained-glass windows?

Almost everything we know about making stained glass in the Middle Ages comes from a 12th-century German monk called Theophilus.

In his text On Diverse Arts, Theophilus (who was an artist as well as a monk), wrote about what he learned from watching glaziers and glass painters at work, so that he could create beautiful windows himself.

To molten glass (made from sand and wood ash) craftsmen added powdered metals in order to change the colour.

The coloured molten glass was blown into a sausage shape, then slit before being flattened into a sheet.

Artists made the intricate stained-glass windows in medieval churches by cutting the sheet glass into shapes. If the artist wanted more detail, they painted them on the glass with black paint.

They placed the pieces of painted and coloured glass onto a design board, and fitted them into strips of lead called cames.

To make the panel secure, the cames were soldered to one another, and the windows waterproofed by inserting putty in between the glass and the lead.

The whole composition was then placed in an iron frame and mounted in the window.

Related articles

Find medieval knights and monsters painted on Narbonne palace ceiling

Seven facts about France's Mont-Saint-Michel abbey as it turns 1,000

Medieval murder and turbulent history of Burgundy’s Semur-en-Auxois