-

How joining a choir in rural France helped me build a new life after retirement

Connexion reader Abigail Gammie explains how singing offered a fun way to make friends – and learn the language

-

Florent Pagny returns with new album and tour after cancer remission

Singer and The Voice star is back with 22nd album 'Grandeur Nature', following his lung cancer remission and vocal recovery

-

Discover the five most iconic French songs everyone loves

From Charles Aznavour to Edith Piaf – find out which tunes made the list

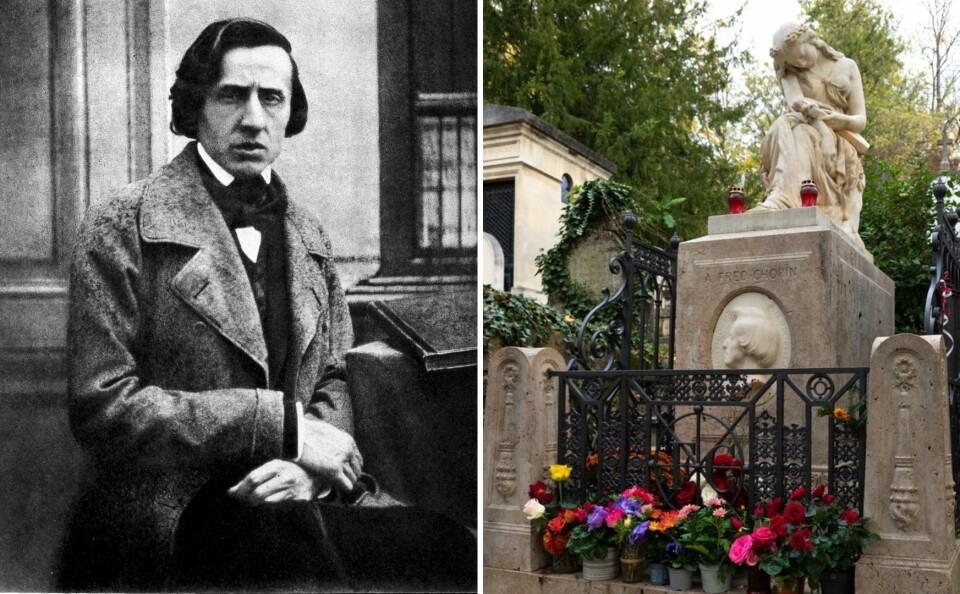

Frédéric Chopin: the short life of a musical genius

We discover the man behind the piano compositions - a child prodigy, Polish émigré and an unconventional love life

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) was born near Warsaw to a French father and a Polish mother.

He left home at 20, fleeing the 1830 November Uprising that saw Polish officers lead a doomed fight for independence from Russia (eventually achieved in 1918).

Although physically frail from birth, he was a child prodigy, giving piano concerts and composing his own music by the age of seven.

He continued to study music and give recitals, performing when he was only fifteen for Tsar Alexander I in 1825.

Having finished his studies at the Warsaw Conservatory, he made his official debut in Vienna, where he received many glowing reviews.

Never became comfortable speaking French

The world was his oyster when he left Poland in 1830. First he travelled to Austria, and then in 1831, having learned that the Polish uprising had been crushed, went to Paris.

His visa was only for ‘transit to London’, but he never went back to Poland, becoming part of the ‘Great Emigration,’ the 1831-1870 exodus of Poles from their homeland.

“I’m only passing though,” he would say to his Parisian friends.

He gained French nationality in 1935, but never really became comfortable speaking French.

His social and professional network included many other famous artists, including Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt. An old friend from Poland, Julian Fontana, became his copyist, and another, Albert Gryzmala, his advisor and mentor.

Read more: From poverty to glory: Life of legendary French singer Edith Piaf

Rothschild banking family opened doors for him

Chopin never had to starve in a garret. He was always recognised for his gifts.

Robert Schumann wrote, “Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!”

Reviewing a concert in 1932, the critic François-Joseph Fétis wrote, “Here is a young man who, taking no model, has found, if not a complete renewal of piano music, an abundance of original ideas to be found nowhere else.”

He was introduced to the Rothschild banking family, who opened doors for him to play in the private salons of the aristocracy and literary elite.

By the end of 1832, he was financially independent from his father, and earning good money from publishing his music and teaching affluent students.

This allowed him to abandon giving large public concerts in favour of playing for friends, either at home or at exclusive salons. He gave fewer than 30 public concerts in his short lifetime.

Put Maria’s letters in an enveloped marked ‘My Sorrow’

In early 1834, he went to Germany, and the following year to Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic, where he saw his parents for the last time.

On his way back to Paris, he met up with an aristocratic ex-pupil called Maria Wodzinska in Dresden. He continued travelling, then returned to Dresden again in 1836, where he proposed to Maria. Apparently she was not interested.

When he sent her a printed album of his music, she responded with the most anodyne of acknowledgements, and that was the last he heard from her.

In true Romantic style, he put the letters he had received from Maria and her mother into a large envelope, labelled it ‘My Sorrow’, and kept it in his desk until the day he died.

Estranged from composer Franz Liszt

The Hungarian pianist and composer Franz Liszt became one of Chopin’s most intimate friends, although Chopin famously objected to Liszt adding musical embellishments to his compositions, and the two became somewhat estranged as time went on.

Chopin’s affair with George Sand surprised them both

In 1836, Chopin met the successful French writer George Sand.

“What an unattractive person la Sand is! Is she really a woman?” he wrote. For her part, George Sand was attracted to Chopin’s fragility and creative genius.

They finally became lovers in 1838, and Sand, who had already had many affairs, wrote, “I must say I was confused and amazed at the effect this little creature had on me. I have still not recovered from my astonishment, and if I were a proud person I should be feeling humiliated at having been carried away.”

It was the start of a love affair that would continue for nine years.

Read more: George Sand: unorthodox literary heroine 19th-century France needed

They travelled to Mallorca that winter, for the health of Sand’s son Maurice and for Chopin. It was not a successful trip, as the devout Catholic locals disapproved of the couple’s unmarried status, the weather was freezing, and Chopin’s health deteriorated.

It was, however, a productive period in terms of the music he composed there.

Creative process of ‘tormented weeping and complaining’

The family went to Spain and then to Marseille where Chopin recuperated. They then travelled to Nohant, Indre, George Sand’s country estate, where they spent most summers until 1846.

Chopin had his own study there, where he was able to compose in peace and quiet.

In Paris, where they spent the winter months, they kept separate households, although they were very often in each other’s houses.

Sand described his creative process as “an inspiration, its painstaking elaboration – sometimes amid tormented weeping and complaining, with hundreds of changes in concept – only for him to return finally to the initial idea.”

They were halcyon years. The painter Delacroix described staying at Nohant: “The hosts could not be more pleasant in entertaining me. When we are not all together at dinner, lunch, playing billiards, or walking, each of us stays in his room, reading or lounging around on a couch. Sometimes, through the window which opens onto the garden, a gust of music wafts up from Chopin at work.”

Sand called seriously ill Chopin her ‘beloved little corpse’

But Chopin was seriously ill. Often exhausted, he spent entire days in bed, and visitors found him doubled up in pain.

From 1843 onwards, he produced fewer compositions. His declining health also affected him emotionally, and his relationship with George Sand deteriorated.

When Sand became more of a nurse than a lover to Chopin, she began calling him her third child, her ‘beloved little corpse’. After nine years together, they split up in 1847.

Read more: Beethoven's ‘skull parts’, found in France, returned to Austria

Escape to grand houses in Britain with former pupil

To escape the 1848 revolutionary uprising in France and to boost his dwindling finances, Chopin went to Britain, where he gave private concerts in the country houses of the elites. This was arranged by his former pupil, Jane Stirling, who also funded the venture.

In London, he performed for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and gave lessons to wealthy pupils. He then travelled to Scotland, staying in grand houses owned by Jane Stirling’s family.

It was not a romantic relationship, however. “I am closer to the grave than the nuptial bed,” he wrote.

He returned to Paris and died aged just 39

He gave his last public performance in 1848 at a benefit concert for Polish refugees.

By this time he weighed less than 45 kilogrammes and his doctors knew that he was terminally ill. He returned to Paris, where he more or less took to his bed.

In the summer of 1849, an admirer, Princess Yekaterina Dmitrievna Soutzos-Obreskova, paid the rent for a flat in Chaillot, outside of Paris, and his sister Ludwika and her family came to look after him.

They all moved back to Paris that autumn, but it was clear that Chopin was dying.

Amongst others, his sister and Sand’s daughter Solange were with him when he died, aged just 39.

A few hours after he died, Solange’s husband made a death mask, and took a mould of Chopin’s right hand.

The funeral was held a fortnight later in Paris, and was attended by thousands.

He was buried in Père Lachaise cemetery, with a tombstone designed by Solange’s husband, featuring the muse of music weeping over a broken lyre.

Ludwika returned to Poland in 1850, taking Chopin’s heart with her. As he had requested in his will, this had been removed by his doctor before the funeral and preserved in a jar of alcohol.

She also took 200 letters from George Sand to Chopin, which she eventually returned. Sand destroyed them.

Modern tests reveal a rare complication of tuberculosis

On his death certificate, the cause of Chopin’s death is tuberculosis.

In 2014, the jar was examined by a team of pathologists and doctors who concluded that he had died from pericarditis, a rare complication of chronic tuberculosis.

The jar containing Chopin’s heart was re-interred in a stone pillar in the Holy Cross Church, Warsaw.

His death mask is in the Fryderyk Chopin Museum in Warsaw; his piano and some of his belongings can be seen at Nohant, which is now open to the public.

More of his personal effects are on display in the Salle Chopin at the Bibliothèque Polonaise de Paris, and the public can visit his grave.

Related articles

‘I played bad classical music because the male composer was famous’

French conductor Zahia Ziouani fights inequality with classical music

Did you know that the Cancan started out as a feminist dance?