-

High-speed rail project, rent controls: Toulouse candidates divided for municipal election

Tight race expected in city as far left home in on quarter of vote share

-

Travelling from France to UK: dual nationals warn over passport renewal issues

It comes as the UK enforces its electronic travel authorisation (ETA) scheme

-

‘If I lower the price I close’: fuel station manager in western France defends €2.97 diesel price

The small station in Deux-Sèvres is selling the most expensive diesel in the country amid the ongoing fuel price spike

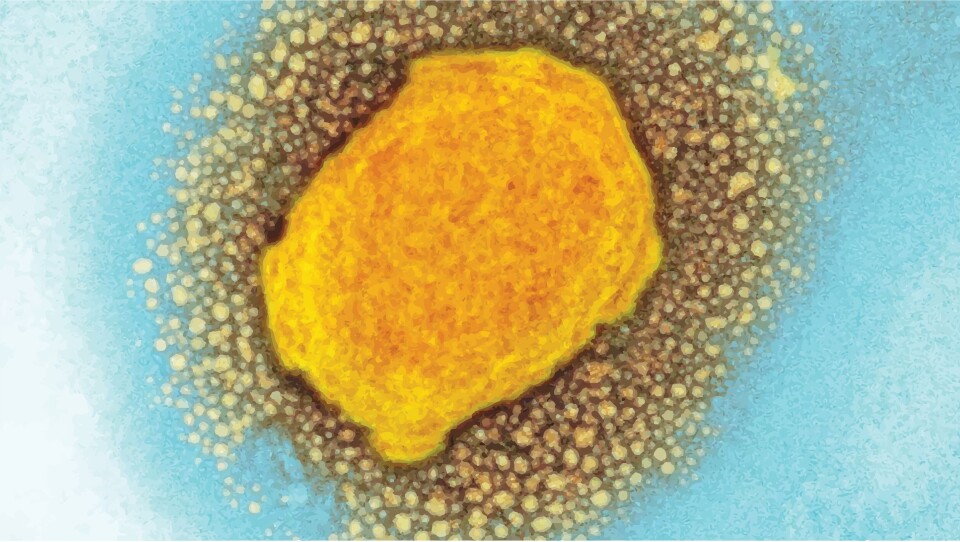

Five monkeypox cases now confirmed in France, risk remains ‘very low’

French health authorities are recommending that health professionals in close contact with cases get vaccinated as a precaution

Two new cases of monkeypox have been detected in France, bringing the total to five.

Three of the infections are in Ile-de-France, with one in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and in Occitanie, public health agency Santé publique France has stated.

Read more:A case of monkeypox virus reported in Paris area, the first in France

Monkeypox cases “without a direct link to a trip to central or western Africa or to people who have returned from such trips have been reported in Europe and in the world, suspected cases are being evaluated in multiple countries and the situation is evolving very rapidly,” it said.

France’s health service quality regulator, the Haute autorité de santé yesterday (May 24) advised adults who come into close contact with confirmed cases – including healthcare professionals – to get vaccinated, a recommendation which will be followed by the government.

The vaccine currently being used for monkeypox is actually for smallpox, a closely related disease.

#Communiqué | Saisie en urgence par @AlerteSanitaire, la HAS recommande la vaccination des adultes et professionnels de santé après une exposition au #monkeypox

— Haute Autorité de santé (@HAS_sante) May 24, 2022

👉 https://t.co/Qc3nlTnTCA pic.twitter.com/CM7nJwtL0C

The European Centre of Disease Control has said that the risk of infection is “very low” among the general population, although “heightened” in people who have several sexual partners.

What is monkeypox?

Monkeypox is a rare viral disease which normally affects rodents and primates in western and central Africa.

It is sometimes transmitted to humans and can be spread via bodily fluids, such as the liquid within the blisters it creates on the skin, or by objects bearing traces of these fluids, such as bedding or towels.

It can also be passed on through droplets from the nose or mouth, but it is not as easily spread in this way as Covid.

In general, close contact with an infected person is necessary if someone is to catch the disease.

The virus begins with a – generally high – fever, often accompanied by a headache, muscle aches and fatigue. After around two days, the rash will appear, creating itchy blisters, then scabs.

Monkeypox’s incubation period can last from five to 21 days, and the subsequent fever phase normally comes to an end after three.

The disease does not normally cause serious illness in infected people, and should go away on its own within two to three weeks. In some very rare cases it can, however, be fatal.

‘Stigmatising homosexual people will harm public health’

Matthew Kavanagh, deputy director of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, has expressed concerns about the way in which the spread of the virus is being linked to bisexual and homosexual men in the media.

News organisations have been reminding the population that the majority of recorded monkeypox cases have been found in men who have sex with men, but Mr Kavanagh told Le Monde: “At the moment what we know is that monkeypox can be transmitted to anyone.

“We are witnessing – on social media but also in some news outlets – an attempt to align the virus with the gay community and to present it as an illness ‘of African origin’.”

He added that, in reality, “it is not an illness which particularly affects a type of person or a type of sexuality. Of course, a large number of the recorded cases up until now have concerned men having sexual relations with other men, but there have also been cases among many different types of people.

“To say that it is a disease which only affects gay men is not correct.

“History has taught us that this type of stigmatisation is likely to lead to a bad public health approach.

“The first consequence is that people will avoid consulting their doctor in fear of being identified as belonging to a certain group.

“In addition, resources are not accorded to some problems which are considered to only affect certain communities.

“Finally, this [messaging] prevents public health officials from really understanding the scope of an epidemic, by not researching cases unless they belong to one particular community, for example.

“One of the first responses to HIV was to recommend closing gay venues. The same thing happened with monkeypox [although not necessarily in France]. But this is an ineffective public health response, as punitive approaches do not really work. What works are open, welcoming services where people can access all the information that they need.

“It is therefore incumbent on the media and on governments to counter these messages with serious scientific information on the real risks of the disease.

Mr Kavanagh also said that the emergence of monkeypox cases around the world showed that “we are not prepared to respond to epidemics as effectively as we should be and we should put in place better preventative measures.”

Read more

Covid vaccines, isolation, tests: What restrictions remain in France?