-

Funeral held in Normandy for last Native American soldier to survive D-Day landings

Charles Norman Shay was among first to land on Omaha beach and a recipient of Silver Star and Legion of Honour medals

-

Tour Alta: the new landmark making waves in Perret’s post-war Le Havre

The tower block sits within a UNESCO World Heritage Site and has sparked conflicting reactions

-

Profile: French supermarket boss Michel-Edouard Leclerc

Modern-day Robin Hood or merciless manipulator of the market?

From Nazi war camp survivor to fêted anti-poverty campaigner in France

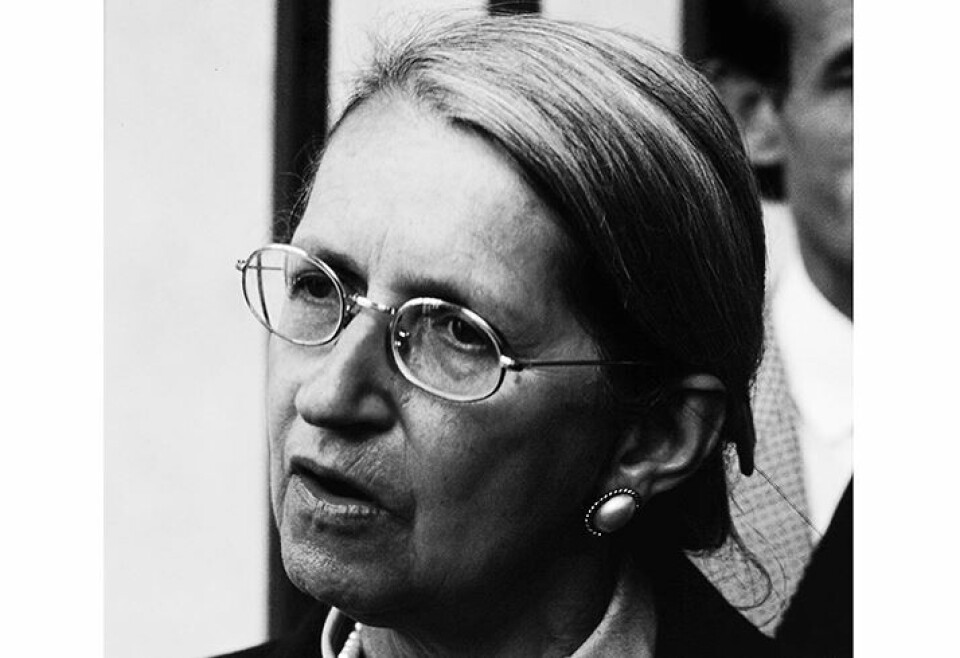

Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, after surviving the horrors of Ravensbrück concentration camp for women, spent the rest of her life fighting to eliminate extreme poverty

Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz (1920-2002) joined the Resistance when she was only 19 years old.

She survived the war, despite spending 15 months in Ravensbrück, the notorious women-only concentration camp.

She spent the rest of her life fighting for the underdog, eventually becoming one of only six women buried in the Panthéon.

Early life

She was born in the remote Cévennes mountains, where her father Xavier, a mining engineer, was the older brother of Charles de Gaulle.

Her mother Germaine was the daughter of novelist Pierre Gourdon.

The family was comfortably well off, educated, cultured and liberal.

Soon after she was born, the family moved to Sarre on the German border, where there was a large mining complex.

As a direct result of the in utero death of her unborn child, Germaine de Gaulle died of septicaemia when Geneviève was barely five years old.

As a result of this tragedy, young Geneviève grew very close to her father. She found it hard to accept her new step-mother when he re-married five years later.

She was a good student, however, and became so accomplished in German that her father got her read Mein Kampf in its original language.

In a referendum of 1935, when she was 15, the population of Sarre voted to become German. (The territory had been held by France since the Versailles Treaty at the end of WW1, but has remained part of Germany since the referendum vote).

After the vote, all resident French citizens were ordered to leave the territory.

The De Gaulle family moved to Rennes, where Geneviève finished school and enrolled to read history at Rennes university.

Joins the Resistance

She completed her first year. In June 1940, when France was occupied, she joined the Resistance using the name Germaine Lecomte.

Early activities included tearing down German posters and Nazi symbols.

She and her fellow students also distributed anti-Nazi leaflets that denounced the Vichy government and the occupation.

In 1941, she moved to Paris, where she enrolled at the Sorbonne and continued her clandestine activities, mainly in the form of writing illicit pamphlets and passing on information.

Betrayed and arrested

She was betrayed and subsequently arrested by the Gestapo, who realised that she was carrying false identity papers.

She revealed her real identity (as a member of the de Gaulle family), and this may have saved her life, as she was earmarked for ransom rather than execution.

Initially held in France, in February 1944 she was transferred to Germany and imprisoned in Ravensbrück.

She formed close friendships with four other Resistance workers: Jacqueline Péry d’Alincourt, Suzanne Hiltermann, Anise Postel-Vinay and Germaine Tillion, all of whom also survived their incarceration.

In October 1944, Himmler ordered her to be placed in solitary confinement while an attempt was made to ransom her back to France.

Liberated

She was eventually liberated when the Red Army arrived at the camp in April 1945.

She spent her new freedom convalescing in Switzerland, where she met her future husband, Bernard Anthonioz, a well-connected, educated, cultured man who had also worked with the Resistance.

They married in 1946 and went on to have four children together.

Her experiences in prison profoundly marked her approach to life.

Back in France, Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz became president of the Association nationale des anciennes déportées et internées de la Résistance.

She felt that it was important to record what people had suffered, as well as celebrate the support and friendship the prisoners had offered each other.

Despite that, it took more than fifty years before she felt ready to recount her own experiences, in her memoir La Traversée de la Nuit, published in 1998.

In it, she detailed the horrors of the three-day cattle-truck train journey to Germany, the guards’ cruelty, and in particular the conditions endured by children in the camp.

Prosecuting war criminals

After WW2, she was deeply involved with the prosecution of war criminals, and also in the Rassemblement du Peuple Français, a political party launched by her famous uncle, Charles de Gaulle.

In 1958, her husband became director of artistic creation at the Ministry of Culture.

Through his work and contacts she was introduced to Father Joseph Wreskinski, a Polish chaplain working in the slum quarters of Noisy-le-Grand, north of Paris.

He had been born in 1917 in a refugee camp in Paris.

His mother was Spanish, his father was Polish but held a German passport, and the entire family had been interned in France during WW1.

He grew up in extreme poverty, and began his path to priesthood at the age of 17.

He was finally ordained in 1946.

As a priest, his self-imposed task was to help the poorest of the poor.

He went into slums and down mines and caught TB.

He went on a pilgrimage to Rome, where he inspected the hellish conditions in Sicilian salt mines.

After returning to Paris, in 1957 he founded the international ATD Quart Monde (Aide à Toute Détresse) which is today known as Agir Tous pour la Dignité Quart Monde.

He coined the phrase Quart Monde (Fourth World) in 1969 to describe the bottom layer of the world’s social pyramid; those people with the least money, rights, and dignity.

Inspecting the slums

He insisted on taking Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz to visit the slums of Noisy-le-Grand.

“On the faces of these men and women I recognised the same look on the faces of my friends in Ravensbrück when we had no more hope, when we were exhausted by the daily struggle, and you tell yourself that it can only end in death...” she said.

“I would never compare a slum to a concentration camp – people were not there to be killed. But when you don’t have water to wash in, no place to sleep, no access to culture, you have experiences which are not far from it. I know the humiliation of feeling bad. I recognised the smell of my friends at the camp among the homeless in Noisy-le-Grand. I knew it well, I had smelt like that myself. When you have experienced absolute evil, the only response is fraternity.”

Life changing

The visit changed the direction of her life.

As president of the French branch of ATD Quart Monde from 1964 to 1998, she was dedicated to eradicating extreme poverty in France.

In 1960, she joined a committee set up by the famous writer Simone de Beauvoir to defend Djamila Boupacha, a young Algerian woman who had been arrested by the French Army on suspicion of plotting a terrorist attack during the Algerian War.

While incarcerated, Mrs Boupacha was tortured, raped, beaten and electrocuted multiple times over many months.

The defence committee shone a spotlight on the illegal and brutal practices of the French authorities in Algeria, and eventually saw Mrs Boupacha released from custody in 1962.

In 1982, Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz testified at the trial of Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie.

In 1988, she joined the Conseil Economique et Social, and spent a decade lobbying ceaselessly for the adoption of the anti-poverty law, the Loi d’Orientation Contre La Grande Pauvreté, which was eventually passed in 1998.

This law led to the establishment of the Revenu Minimum d’Insertion (RMI), the Couverture Maladie Universelle (CMU), and the Droit au Logement Opposable (DALO), all of which aim to prevent exclusion and destitution.

She was awarded the Grand-Croix de la Légion d’Honneur, the Croix de Guerre 1945-1939, the Médaille de la Résistance Française avec Rosette, and the Prix des Droits de l’Homme.

Death

She died in 2002, and was buried at Bossey (Haute-Savoie).

A memorial plaque was installed on the house where she lived in Paris.

She was so highly regarded that she was even considered for canonisation, though this was not pursued.

In 2015, President François Hollande announced that Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz’s remains were to be transferred to the Panthéon.

Her old friend from Ravensbrück, Germaine Tillion, was also to be reinterred there.

The families decided not to allow their ancestors’ remains to be moved, however, and therefore the two women symbolically entered the Panthéon in May 2016.

The coffins used contained only earth from the cemeteries where the respective women were laid to rest.

Related articles

The remarkable WWII story of a British secret agent in occupied France

‘I drew in five minutes the absolute pain of a lifetime’

Simone Veil: a force for good, for women, for France, for all