-

Exotic ‘lipsticked’ song bird spreads across south-west France

Sightings and hearings of the Rossignol du Japon have caused a Facebook sensation, especially in and around the Pyrenees

-

Hunting by bow is expanding in France: rules and licences

40,000 hold a permit to hunt with a bow and arrow

-

Duck Cold! Four French phrases to use when it is freezing outside

We remind you of French expressions to use to describe the drop in temperature

Snakes, wader birds and the wrath of hunters in French countryside

Wildlife spotter Jonathan Kemp shares stories of reptiles, raptors and four flat tyres

Walking at the edge of a freshly mown corn field, suddenly the dogs leapt up and recoiled a little.

Just behind them there was a snake, head and body raised, slithering through the stubble, clearly alarmed by the canine presence.

Instinctively the dogs are afraid of snakes, but just to be sure, I called them away and the snake dropped out of view.

My view was but a glimpse, but I am pretty sure that it was an Aesculapian snake, a grey green colour with a smooth head, fairly large, they can be up to two metres long.

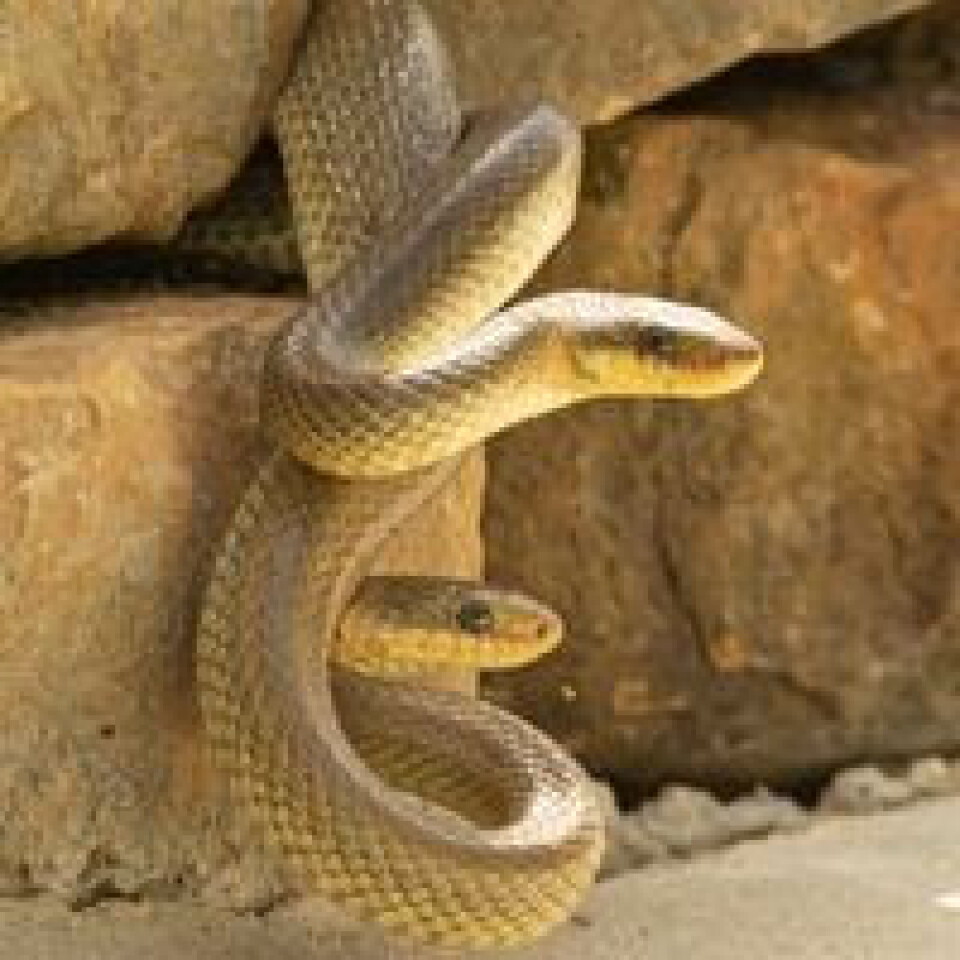

No doubt it was in the field to hunt mice and rats, and even though I searched I was unable to find it again, probably it found a rat hole to slither down and hide in. Below is an image a friend took of a pair of mating.

Photo: Adrian Henderson

Aesculapian snakes (Couleuvre d’Esculape) are diurnal, non-venomous, rarely aggressive (although the name derives from the Greek for angry, irritable) quite capable of climbing trees, preferring to hide away when in contact with humans.

Note the round pupil of the eye, this is generally, but not always, a giveaway that this is not a venomous snake; a viper’s (Vipère aspic) being more slit like in appearance, and this is useful for identifying the different snake species that we have in France.

Read more: Body of 1.5 metre python found on roadside in northwest France

Declining snake population

A friend who as a young man 50 years ago used to collect adders in the wild in order to send them to the Marie Curie Institute to produce anti-venom (this is no longer done, rather a population of snakes are kept in captivity and regularly ‘milked’), says that snakes are much less common than they were.

He wonders if this is linked to the increase in raptor populations, but no doubt there are other factors involved, the danger of roads being one, destruction of habitat another.

Read more: How do I report driver in France who ran over snake?

The best time to see snakes is in the morning, as they need to bask on warm stones in the sun to thermoregulate, in order to become active and to help them digest any prey that they have swallowed.

A symbol of healing

Historically Aesculapian snakes are associated with the classical god of healing (Greek Asclepius and later Roman Aesculapius) and are symbolically depicted entwined around his staff to signify healing and medicine.

Why this is seemingly obscure, however, it is known that the species was encouraged in the vicinity of temples dedicated to the gods; being non-venomous there was no danger to devotees, or the sick people that gathered there.

Lizard encounter

Whilst sitting quietly watching to see whether there was an eaglet in a Golden eagle nest that I visit I was happy to see a lizard crawling over my leg.

It is a Wall lizard (Lézard des murailles), content to use me as a perch for a while.

Wall lizard on my knee; Photo: Jonathan Kemp

The end of another breeding season

As the breeding season winds down the songs and cries that greet me each morning as I wake become less urgent, more occasional.

We have been delighted this year with Golden Orioles (Loriot d’Europe) nesting very near the mill, and their lovely fluting whistle has continued long into the summer.

Golden Oriole; Photo: Claude Ruchet

A difficult bird to see, even the brilliantly coloured yellow males hide too well amongst the sun dappled leaves at the top of the trees where they prefer to perch.

Soon they will go back to tropical Africa where they stay over winter.

Wader birds’ paradise

On the border of the departments of Aude and Hérault is the best wetland for many kilometres around.

An extensive low basin of interlocking lagoons, divided by reed beds, some dirt tracks crossing it, small villages around the circumference; it is a wader birds’ paradise.

Aptly named Black-winged Stilt, (Echasse blanche), prancing along on his absurd bright red ‘stilts’; Photo: Jonathan Kemp

The water level does slowly drop throughout the summer, exposing more mudflats before they dry up. Becoming shallower, they give compensatory access to the shorter legs and beaks of some of the species that choose to nest there.

No doubt, in very dry years, when the young have been raised to independence, the numbers of birds will diminish to fit the limited food supply that remains, the rest flying off to search for less crowded habitats to feed.

The exotic Glossy Ibis (Ibis falcinelle), looking more like a bird from an African lake rather than Europe; note the dark velvet sheen of the adult’s summer plumage, on the right; Photo Jonathan Kemp

Humans mark their territory too

About 20 years ago a friend who lives nearby contacted me and a couple of others to report a rare raptor that was hunting on the wetland at the time, seldom seen in France, a Black-winged Kite (Elanion blanc).

We drove down and had good views of this hobby sized raptor as it hovered in search of the insects and lizards that are its main prey.

As I drove away I found that I had a slow puncture; reaching home an hour later it was clear that all four of the tyres were slowly deflating; they had been pricked with a needle and in fact all of them had to be changed.

I had learnt to my cost that this wonderful wetland was controlled by a hunting association (Syndicat de Chasse) who had no intention of sharing the area with anyone else, and would go to such dangerous lengths to maintain exclusive control.

Consequently it is little visited outside of the hunting season, and only the most intrepid birders go there making sure that they leave any vehicles out of harm’s way.

I was advised by the LPO that it was best to keep away, so entrenched was the hostility that there was a danger that non-game species would be shot to discourage visitors.

But there are signs that things have improved over the last couple of decades.

Hope for the future

I happened to be nearby recently so took my lunch and drove to a suitable spot by the lagoons.

The birds were amazing, not shy of me, which they would be if the hunting was still fierce, there was a party of children taking a picnic nearby, and there was a group of walkers ambling along one of the tracks in the distance.

So fingers crossed, the next generation of birders will be allowed to share the richness with those that wish to harness it for sport.

Related articles

Hunting subsidies rise to €6.3m in France as critics call for ban

National parks in France warn visitors to respect flora and fauna

Fears the Giant American bullfrog will damage native French wildlife