-

Rugby vocabulary to know if watching the Six Nations in France

From un tampon to une cathédrale, understand the meaning of key French rugby terms

-

How joining a choir in rural France helped me build a new life after retirement

Connexion reader Abigail Gammie explains how singing offered a fun way to make friends – and learn the language

-

Duck Cold! Four French phrases to use when it is freezing outside

We remind you of French expressions to use to describe the drop in temperature

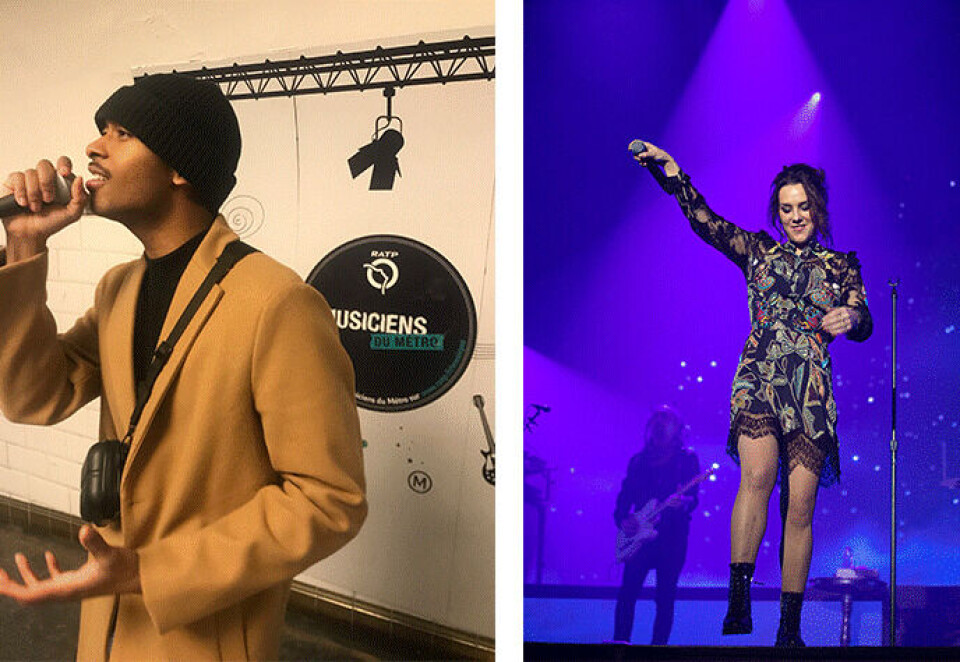

Why Paris metro busking can be a career springboard for musicians

We talk to two buskers about why they do it – and how much they earn

The thermometer shows 1C and it is 13:00.

René Miller unfolds his chair and unzips a guitar from its case, along with a bottleneck, capo and thumb pick.

Everything is ready for four blues songs straight from the Mississippi Delta.

His ‘stage’ is not the American South, but Croix de Chavaux, a metro station on line 9 in Montreuil, in the eastern suburbs of Paris.

“I usually never play below 4C, but I will make an exception for you,” said the 59-year-old US guitar player with 14 CDs to his name.

Read more: Paris classed ‘world’s third most musical city’ in new ranking

The next day presented an opportunity to shadow the enthusiastic Tony Moreau, 23, who set up his microphone and speaker on a small handcart at Châtelet station for two sessions between 10:00 and noon.

Mr Moreau and Mr Miller are just two of a number of American artists busking around Paris metro stations, although they have contrasting opinions about the opportunities these gigs present.

Heyday well and truly over

Mr Miller will tell you that the heyday for Paris buskers is well and truly over, destroyed by the cumulative effects of the 2015 terror attacks and Covid pandemic as well as the digitalisation of payments, leaving fewer travellers with cash.

It was not always the case.

He recalls making “good money” – around 100 francs a day – when he came to Paris in 1990, after kicking off his busking career in Berlin.

At that time there was a buzzing music scene, which helped him find a drummer and bass player overnight.

There was also a great social life, with buskers typically reconvening after performances at Le Mazet, a bar in the Odéon district.

While Mr Miller is still happy to busk, he has lost some of the enthusiasm that newcomers such as Tony Moreau exude.

Mr Moreau, who is studying for a Masters in international business, has been living in Paris for 18 months and plans to make a living from his singing after all the practice.

“I want to be New York-ready for 2025,” he says.

New generation of buskers more social media savvy

His catalogue is fresher, featuring songs from John Legend and Alicia Keys, and adapted to the online age – his Instagram handle and Paypal QR code are both emblazoned on his suitcase.

It works. People pause to listen to his voice, film his performance and post videos on social media.

Crucially, they also show their appreciation by digging into their pockets.

He was given a €20, a €10 and a €5 note during the course of a single song.

Both buskers are members of Musiciens du Métro, a label founded in January 1997 comprising 300 artists playing in Paris metro stations.

Big names have started their careers here, including singer-songwriters Keziah Jones and Zaz, Claudio Capéo and Clémént Verzy, winner of the French version of The Voice in 2016.

Every September/October and March/April, busking hopefuls perform in front of a Musiciens du Métro jury, which allocates licences to successful candidates.

Audition to win busking rights

The audition comprises two songs of the musicians’ choice.

If successful, the licence gives them the right to play at any time during metro service, for as long as they wish and for no charge.

Buskers can leave a cap or bucket in front of them to collect money, but are not allowed to perform on the trains, nor on the platforms.

It is a six-month accreditation, with the artists free to renew it as often as they want.

Musiciens du Métro says it renews its membership by about a third every six months. The artists come from various backgrounds, not just French, and with a range of musical skills.

The jury looks for technical ability and originality, and tries to represent a variety of music, from rock to classical.

Antoine Naso, who started the scheme, said: “There have been buskers in the metro since it was built but at first they were illegal and a nuisance.

Improved quality

So we created this scheme to improve quality.

Read more: Mythbuster: French music cannot survive outside France

“Above all, we are looking for something that will please passengers as, first and foremost, we are a transport authority.”

He said buskers do not usually make enough money to live on but it is an opportunity to improve their skills.

“It is harder to play on the metro than on a stage with a static audience.”

Mr Miller says he no longer performs with a view to becoming famous, but he sometimes dreams of travelling again.

His metro set attracts some applause and a few coins but he does not bother to count them, guessing at around €6.

He is returning to the US temporarily from February to work in a DIY store and supplement his busking income by some $6,000 to $7,000 in the process.

It will mean he can afford his Montreuil rent for another nine months. As he pragmatically explains: “You gotta eat.”

Related articles

From poverty to glory: Life of legendary French singer Edith Piaf

French festivals ‘could be cancelled’ during 2024 Paris Olympics

Four albums recorded in France and one song that should have been