-

Paris group promises help to ‘live your best life’

WICE is a vibrant English-speaking community offering classes, workshops, and social events to help expats integrate and thrive

-

Transavia to replace Air France for Nice-Orly flights

Up to eight return journeys a day to be offered by the budget carrier

-

+39% increase: Paris sees major parking cost changes in 2026

Arrondissements in the east saw the largest increase in costs

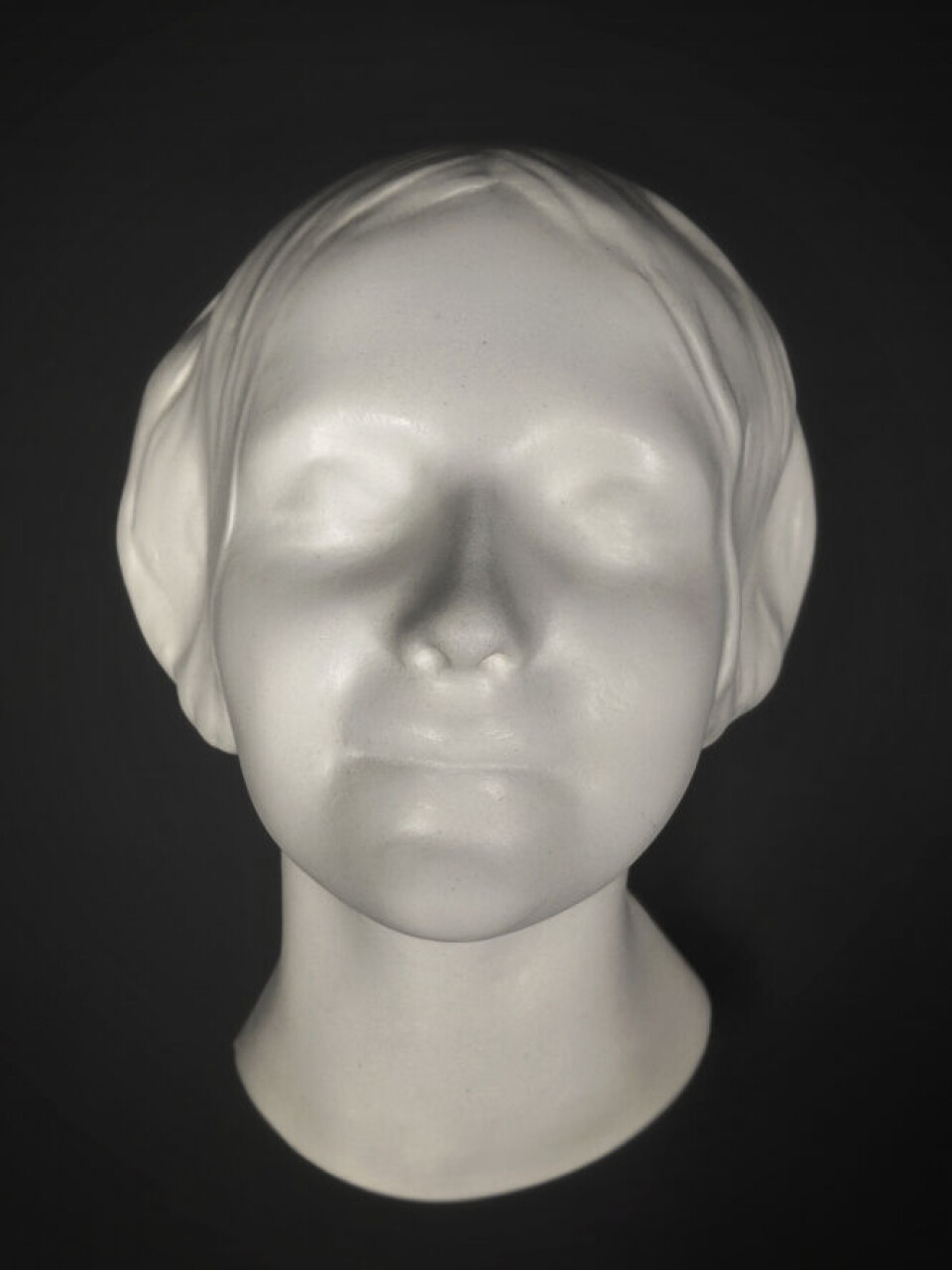

Journées du patrimoine: Meet the maker behind world's most kissed face

This Parisian moulding workshop – open for one day this weekend – may hold the original mould of the Inconnue de la Seine, an unknown woman drowned in the 19th century whose face has inspired novels, artwork and even CPR dummies

This weekend, Ile-de-France’s monuments and museums will be inviting members of the public to view their most treasured collections as part of the 2021 Journées du patrimoine (European Heritage Days) programme.

On September 18, visitors will be welcomed to the renowned moulding workshop Atelier Lorenzi, for a rare glimpse into a business that has for 150 years been creating reproductions of some of the world’s most precious artworks.

We spoke with atelier director Eric Nadeau about the workshop’s rich history, and its part in the mysterious tale of the Inconnue de la Seine, a facial mould of an unknown woman recreated thousands of times across novels, artwork and Resusci Anne, the CPR dummy.

The Connexion: The Atelier Lorenzi has been around for 150 years, creating, reproducing and restoring the artworks of more than a century of cultural and social movements. How was the workshop first founded?

Eric Nadeau: “The Atelier Lorenzi dates back to 1871 and was founded by Michel Lorenzi, who was from an old moulding family based in a small village near Lucca, Italy and arrived in Paris around 1850.

“In 1871, the Paris Commune had tried to narrow the huge social discrepancies between the city’s poor and rich, and had spent three months destroying things that were of value to bourgeois people. Once it was suppressed, Paris underwent a transformation. Small streets were enlarged, buildings gained new façades with lots of statues for decoration. This is the haussmannien Paris that we know today.

“This time also saw the rise of the bourgeois salons, places which allowed people to show off how cultured they were. Not everyone was able to buy magnificent pieces of historic art, but they were able to buy copies.

“So, this was a perfect time for mould-makers and the Lorenzi family. Michel Lorenzi founded his workshop at 19, Rue Racine, soon expanding to No. 21 as well.

“It became quite a famous workshop and it was a very profitable business. Michel had two sons, Charles and Pierre. Charles was an alcoholic poet-type who was friends with the likes of Guillaume Apollinaire and the Parnassian group.

"He had a wonderful personal collection of moulds, and because he did not get on with his father and brother he decided to go his own way and set up his own workshop at 119, Boulevard Montparnasse. We still have one of his old catalogues in the workshop today.”

Nowadays, the Atelier Lorenzi is located in the southern Parisian suburb of Arcueil, in a building that dates back to the 1940s.

“We work with companies, museums, collectors and artists. Religious institutions sometimes ask us to come and repair a broken statue and things like that. Last year we even did a mold of some sneakers. You can mould almost anything!”

The Connexion: What is the best thing about being part of the moulding industry?

Eric Nadeau: “I love being in touch with the world of art history. Statues from Ancient Greece or the Renaissance or the nineteenth century become familiar to us, almost like close friends - or enemies! They are like living beings for us.

“My favourite piece is François Pompon’s ‘The Great Deer’, which I have a wonderful copy of. I have a huge collection of François Pompon’s work; he was a very interesting animal sculptor who was active between 1921 and 1933. Before that he worked for the sculptor Auguste Rodin, but in his retirement, he became very poor and had to do something. So he became a great artist!”

The Connexion: What role did the workshop play in the mysterious story of the Inconnue de la Seine?

Eric Nadeau: “The Inconnue de la Seine is the highlight of our workshop tour. In the late 1800s, the body of a young woman was found floating in the Seine river. The story goes that she committed suicide because of a broken heart. Either way, the body was taken out of the river and to the Morgue of Paris, which was then behind the Notre-Dame Cathedral.

“The pathologist at the morgue examined her body for the death certificate and was touched by her serenity, her beauty, the quiet smile on her face. It is very rare that you find such a pretty face on a drowning victim because the water really affects the look of their skin.

“So, the pathologist asked for a mould to be made of the young woman’s face and the closest moulder was our very own Michel Lorenzi at 19, Rue Racine. So, Lorenzi made a mould and gave the cast to the doctor. The mould went back with him to his workshop and he decided to put a cast of the girl’s face in his window.

“Between 1902 and 1907, Auguste Rodin ran a workshop in Meudon on the outskirts of Paris, employing an Austrian personal secretary called Rainer Maria Rilke, who was also a writer and poet. Every day, on his journey to Meudon, Rilke had to pass through Rue Racine and in front of Lorenzi’s shop window.

“In 1910, he published a short novel called Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge (The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge): the story of a Danish student studying philosophy at the Sorbonne. While walking round the city, Brigge ends up in front of a shop window on Rue Racine, displaying the face of a young woman who died some time ago, perhaps of a broken heart.

“The novel was popular in German-speaking countries but not in France. Mr Lorenzi started to receive orders for the face of this young lady from Berlin and Dresden, from Vienna and Prague, and he did not know why.

“Then, during World War One, two soldiers on the Western Front spent their nights drinking wine and dreaming up a new aesthetic. Those two soldiers were André Breton and Louis Aragon, and their imaginings would become Surrealism.

“On their return to Paris, the two poets began searching for things that would give meaning to their artistic movement. One day they happen upon a shop window at 19, Rue Racine, where they see the mask of a long dead young lady with no name.

“André Breton says: ‘This is wonderful! I love it, this is Surrealism!’ He and Louis Aragon rush into the shop to buy a mask and as their artist friends get to know about it, the Inconnue slowly becomes a symbol for the whole movement.

“The face of the Inconnue began to be reproduced in Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Finland, Sweden and finally Norway, where she ended up in the hands of a toymaker called Asmund Laerdal.

“Mr Laerdal – [who coincidentally had rescued his own son from drowning] – was working on a mannequin for teaching CPR. He used the face of this beautiful young woman for the puppet, and now in the UK and North America, you learn how to do mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on the Inconnue, also known as Resusci Annie or Rescue Annie.

“So she is the world’s most kissed woman!”

Related stories

‘I was very excited about the idea of creating a museum from scratch’

'Patience and creativity' needed to create stonemason art from France