-

Reader feedback: do restaurants in France cater to gluten-free diets?

Allergens are not usually indicated on menus

-

Grand crème, café crème, au lait: how to order coffee in France?

We explain the subtle distinctions between the various terms used in cafés

-

What is ideal calendar donation for French firefighters and postal workers?

There is no set price for the calendars, which are sold in workers’ spare time

Do people still celebrate their name days in France?

It is a French tradition to send people good wishes on their ‘name day’. We look at where this came from and whether the custom continues today

Reader question: I’ve heard people celebrate their saint name days in France. Where does this tradition come from and are you expected to send friends your good wishes on their name day?

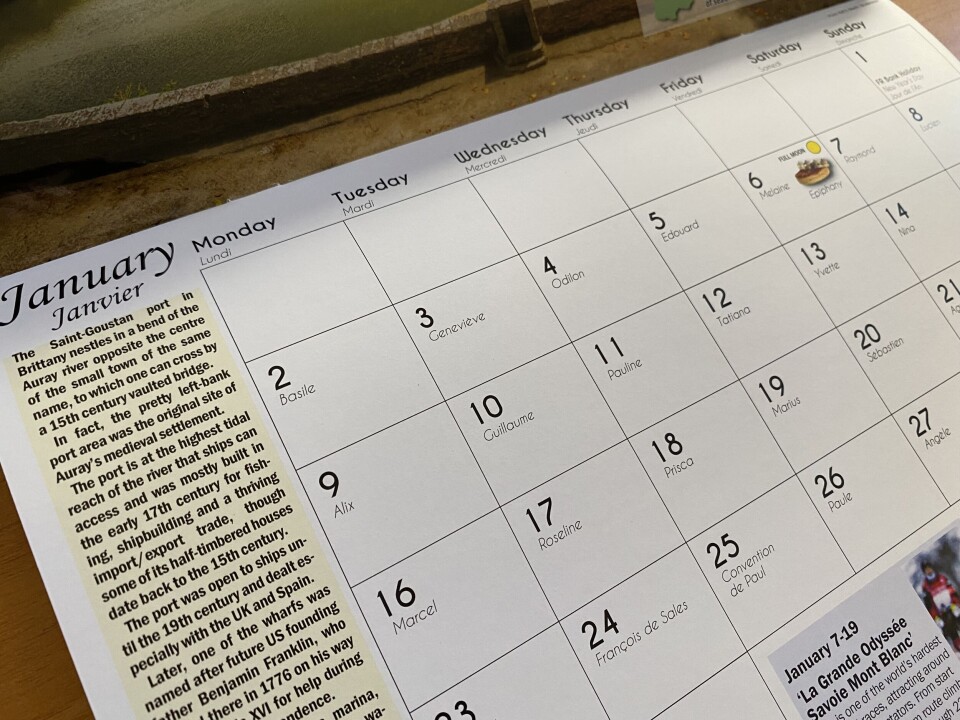

If you have ever consulted a calendar in France, you will probably have noticed that there is a name attached to each day.

As you say, this is the name of a saint, and if you happen to share the name which appears on the calendar on a given day, it means it is ta fête (your celebration / name day).

While this might seem like people in France get to celebrate their birthday twice, it is not such a big deal, at least not anymore.

The tradition stems from the practice in early Christianity of assigning a day to celebrate each new saint as they were canonised.

Usually, this would mark the day of the saint’s death.

Eventually, during the Middle Ages, there were enough saints to have one for each day of the year.

Today, there are so many that many days honour several saints.

It is unclear exactly when Catholic societies began celebrating people with the same name as well as the saints themselves, but in France this was facilitated by the fact that most people were named after a saint.

On 11 Germinal An XI (April 1, 1803), Napoleon introduced a law that required children to be given “names used in the different calendars, and those of well-known figures from ancient history”.

He was supposedly angered by the number of people giving over-patriotic names based on figures of the French Revolution to their children.

This was occasionally a cause for confusion. In certain French colonies it became a tradition to name your child after the saint from the day they were born.

This led to some children born on July 14 being called Fetnat, as the Fête Nationale celebrations were abbreviated to Fêt.Nat on the calendar.

New law granted freedom to choose (almost) any name

Although a number of reforms in the second half of the 20th century relaxed this rule slightly, it was only overturned completely in 1993, when a new law granted parents in France the freedom to choose (almost) any name.

Since then, parents can only be prevented from choosing a particular name if it appears ‘contrary to the child’s interests’.

Examples of names which have not been allowed include Fraise (strawberry) and Nutella.

A judge did, however, decide in 1999 that the Renaud family could call their daughter Mégane.

Even if it is rare to give somebody a present, it is still common, especially among older generations, to phone friends and relatives on their name day.

It is not seen as a social obligation, and people will not be irked if you neglect to wish them bonne fête, particularly as many people these days are not named after saints.

Sending well wishes is more something you might do if you happen to notice the name on the calendar and it gives a nice excuse to phone somebody you might not have spoken to in a while.

Certain people will even wish you a bonne fête the day before your name day.

One possible explanation for this is that services for the most significant days of the Christian calendar, such as Christmas, begin with the ‘first vespers’ the evening before, and this tradition was extended to all saint days.

Related articles

Mark your calendar: Holidays and days off in France in 2023

What is Toussaint day, when is it and why does France celebrate?