-

We went to a French curry house but it didn't hit the spot

Columnist Samantha David laments the lack of decent meals in the style of the subcontinent

-

From 'romantic Paris' to dating apps: love is changing in France

Researcher Aziliz Kondracki explains the role that romance plays in modern France

-

Costume, music, floats: where to see France’s vibrant carnival parades

Celebrate the end of winter with feasting and fun at a carnival near you

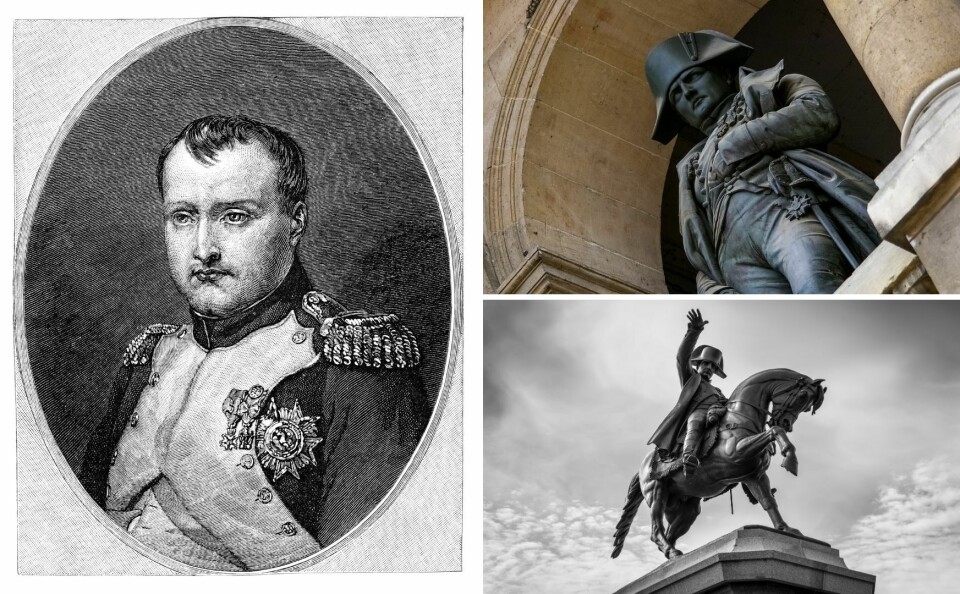

Napoleon, an ‘irritable little tyrant’? Not to us French people

The leader remains a central figure and unified France during one of its most fraught periods, say two experts, as a new blockbuster film about him divides critics

French people have a positive view of Napoleon despite his polarising legacy, two historical experts have told The Connexion ahead of a new blockbuster film which is dividing critics.

The Connexion reviewed French people’s views of Napoleon after noticing the contrast in responses from British and French newspaper cinema critics about Napoléon, the new film from legendary British director Ridley Scott.

British critics appear to have loved the film, while the French response has been much more negative.

The film comes out in cinemas today (November 22), and stars US Academy Award-winning actor Joaquin Phoenix in the title role. Academy Award nominee Vanessa Kirby plays his wife, Empress Joséphine.

Divisive figure

The lack of critical consensus is perhaps not surprising, however, considering Napoleon has been one of the most studied, commented and divisive figures among historians.

He has been the subject of more than 700 films and more than 80,000 books - more than the number of days since he died.

“There is a very Anglo-Saxon vision of the man, as a tyrant exercising dictatorial power, but also as an ill-mannered human-being with childish behaviours,” said François Houdecek, special projects director at the Fondation Napoléon, and author of two recent books about the leader.

This view aligns with comments made by Mr Phoenix, who told the Agence France-Presse that the leader was “an irritable little tyrant”, who behaved like a “teenager in love”, and had an “immature side”.

‘Reformer and military genius’

But Thierry Lentz, a director at the Fondation Napoléon, has lambasted the film in Le Figaro, saying that it is a historical mistake to attribute all of Napoleon’s decisions, ambition and destiny to the circumstances of his relationship with his wife Josephine.

Mr Houdecek would appear to agree, stating: “Napoleon was a reformer, a military genius, a legislator, an administrator, the founder of an empire, a sovereign, a diplomat and the head of a State. All of this has been ‘dialled down’ in favour of a more ‘human story’, which is not very convincing.” In fact, these more positive adjectives are actually how most French people remember Napoleon, he added.

“Napoleon embodies unity to the French people. He united those who were nostalgic for the Ancien Regime [prior to the 1789 Revolution] with those who were sympathetic to the Revolution, and united Republicans with monarchists,” said Mr Houdecek.

“He also embodies a certain form of the country's grandeur; a great man coming at the right time.”

This taps into a characteristic of French people, who have typically looked towards powerful figures to rule the nation - such as Charles de Gaulle and Louis XIV.

‘A parody’?

Sophie Muffat, one maritime expert at the Fondation Napoléon, told The Connexion that in her view, the film is simply an “artistic work”.

It “looks aesthetically accomplished” but is only “a parody - in the literary meaning of the term” and should only be seen as “a reinterpretation of events in a Shakespearean style”, she said.

She added that she had noticed some historical mistakes and artistic liberties being taken.

Differing critical responses

The Fondation Napoléon’s less-than-positive opinion of the movie appears to align with the poor reviews seen in most French newspapers, including strong rebuttals from Le Figaro, Libération, and Télérama, whose critics gave the film their lowest rating.

In contrast, British newspapers, including The Guardian and The Times, were full of praise.

For example, The Guardian critic Peter Bradshaw wrote: “Ridley Scott – the Wellington of cinema – has created an outrageously enjoyable cavalry charge of a movie, a full-tilt biopic of two and a half hours in which Scott doesn’t allow his troops to get bogged down mid-gallop in the muddy terrain of either fact or metaphysical significance, the tactical issues that have defeated other film-makers.”

The Times called the film a “new eye-gouging spectacular historical epic from Ridley Scott”.

But Mr Houdecek said that director Mr Scott did not consult the Fondation Napoléon while making the film. And, even among historians - both French and foreign - there is considerable disagreement over the characteristics of a leader whose ‘larger-than-life’ life arguably perfectly suits the drama of the cinema.

‘Were you there? Then how do you know?’

Ms Muffat said French society is divided into three main opinion groups.

The first two groups are either nostalgic for Napoleon, or hate him. They have polar opposite views on the leader, either downplaying or emphasising his so-called ‘negative effect’ on France and the world, including the millions of war casualties and the use of slaves.

“So far, what I see is that 'the nostalgics' hated the movie, but Napoleon’s critics loved it,” said Ms Muffat.

The third group are historians who portray a particular view of the leader, and add fuel to the debate around Napoleon's divisive nature, both Mr Houdecek and Ms Muffat said.

“Ridley Scott portrays Napoleon as a child crying a lot when he was very cold. Seeing him crying a lot during his private moments is very strange,” said Mr Houdecek.

Ms Muffat agreed. She said: “That human aspect is not based on facts. It is a perception.”

For his part, Mr Scott has said that the history is open to interpretation, and questioned people who say his portrayal is incorrect. In an interview with the BBC, he has rebuked criticism from historians by asking: “Were you there? Oh, you were not. Then how do you know?”

Related articles

Map: Where in France do people give most to charities?

Homeless in France get accommodation in offices when workers go home