-

All Saints’ Day: American war cemetery in north-east France hosts grave sponsorship event

Members of the public can discover the story of their service member, in exchange for flowers

-

How to buy a 2025 remembrance poppy in France

The Royal British Legion has several branches in the country. You can also buy a French bleuet

-

Discover Verdun's Memorial Museum and Douaumont Ossuary

Why the museum is the best place to begin your exploration of the battlefields

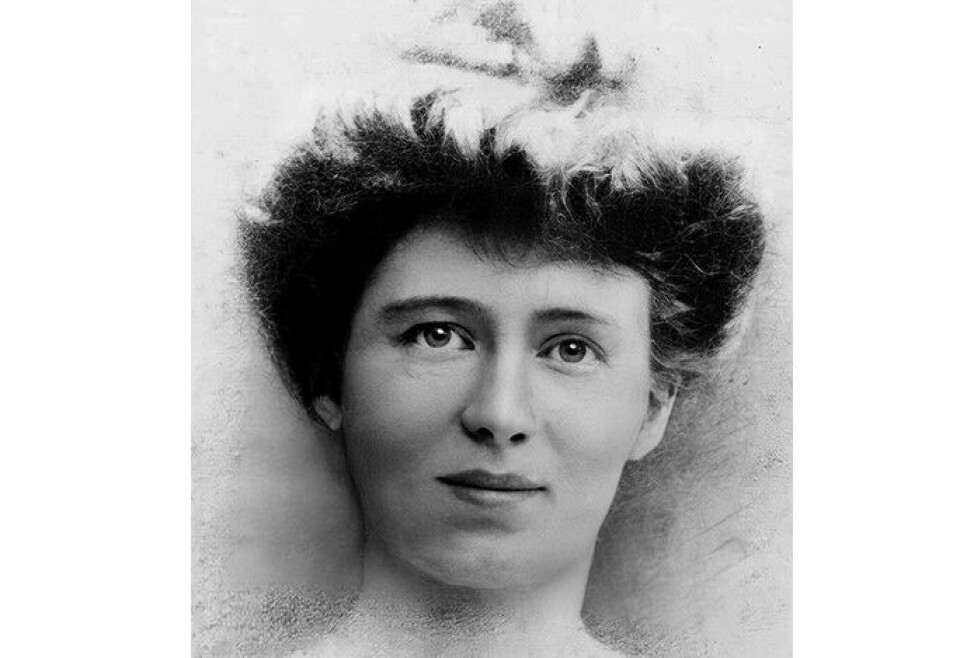

The female French spy who saved more than a thousand British soldiers

In WW1, Louise de Bettignies worked undercover for the British secret service. We look at her heroic life

Louise de Bettignies (1880-1918) was a French spy who worked for the British during WW1 using the alias Alice Dubois. Born in Saint-Amand-les-Eaux, north of Valenciennes, she was the seventh of eight children. Her father was a captain in the army and owned a fine porcelain factory.

She was educated as a boarder at the Couvent de la Sainte-Union des Sacrés-Coeurs in Valenciennes. When her parents moved to Lille in 1895, Louise was sent to another convent, this time in England. She went first to Upton in Essex, then to Wimbledon, and finally to Oxford.

Talent for languages

When her father died in 1903, she moved back to France and finished her education at the University of Lille, graduating in 1906. A talented linguist, she spoke fluent English, Italian and German, as well as some Russian, Czech, and Spanish.

She then began a career as a governess, working for the Comte Visconti di Modrone in Milan. While there, she managed to travel extensively all over Italy.

She was successful in her career. In 1911, she went to work for Count Mikiewsky near what is now Kyiv in Ukraine, but which was at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

She then worked for Prince Karl Schwarzenberg in Orlik Castle, in what is now the Czech Republic, and in 1912 was employed by Princess Elvira of Bavaria at the Holleschau Castle, where she met Rupprecht, the Crown Prince of Bavaria.

She was offered a post as governess to the children of Archduke François Ferdinand, first in line to the Austrian throne. But it was 1914, and everyone in Europe knew that storm clouds were gathering.

1914 and storm clouds gathering

She declined the offer and returned to France where she underwent surgery for appendicitis.

Her family had disintegrated. Her sisters had left home, and her mother was living with one of her brothers. She moved in with her brother Albert in Wissant with the intention of becoming a Carmelite nun.

But by the time war was declared, she was back in Lille, 34 years old, living with her sister Germaine and a mutual friend called Germaine Féron-Vrau who managed the local Ligue Patriotique des Françaises and who had founded the Red Cross Hospital in Lille.

Germaine recruited both sisters as nurses, and Louise is known to have written letters dictated by dying German soldiers to their families.

Starts to smuggle letters

When Lille was occupied by the Germans in October 1914 and cut off from the rest of France, the Bishop of Lille asked Louise to carry letters out of the city to civilian refugees. She agreed, and made many journeys, but was eventually arrested in Péronne by the Germans.

Luckily however, she recognised Rupprecht of Bavaria amongst a group of officers who, remembering her, gave her a laisser-passer. With this document she travelled through Belgium and Holland to the UK.

Introduction to the British secret services

Arriving in Folkstone, she was questioned by the authorities and introduced to the secret services, who were impressed by her linguistic skills, knowledge of Europe, courage and patriotism.

She spent some days in Folkstone doing a rudimentary course in espionage techniques, took on the alias of Alice Dubois and went back to France posing as an employee of an import/export company.

Swiftly infiltrated into the occupied zone, she set up an extensive network called Ramble to collect intelligence for the British.

Based in Lille, her contacts extended in all directions, even as far as 40kms behind the German lines – her network was the most efficient of WW1.

Read more: Violette Szabo: British spy who fought Nazis to avenge French husband

Saved more than a thousand British soldiers

It involved between 80 and 100 people from all levels of society, and is estimated to have saved the lives of more than a thousand British soldiers between January and September 1915.

Read more: The American who was a Schindler in France

The network gathered information on German troop movements and operations, organised accommodation and transport to the Front for agents, recorded train movements, and intercepted post and clandestine press.

Once a month, Louise went to Folkstone with messages written in tiny writing in code on cigarette papers, which she hid in her shoes, the whalebones of her corset, the lining of her handbag, the heel of a shoe, or inside her hair accessories.

When Wilhelm II, the German emperor, made a top secret visit to the front lines, the network knew the exact date and time, enabling the UK air force to bomb the train. (They missed their target.)

Read more: Did you know? A decoy Paris was planned in WW1 to trick German bombers

In one of the last messages she sent, she warned the French that the Germans were planning a massive attack at Verdun for early 1916. They didn’t believe her.

Her closest friend and co-conspirator Léonie Vanhoutte was arrested in September 1915, but in October, Louise went to Belgium as planned, carrying letters for Britain.

Swallowed secret message

At a station checkpoint near Tournai, the soldiers were making female passengers undress to be searched. As she undid the back of her dress, Louise slipped a ring off her finger, removed the secret message concealed inside and swallowed it.

She had been seen, however, and was arrested and ordered to swallow an emetic. When she refused, she was hit in the stomach by a rifle butt causing serious internal injuries.

Imprisoned in Tournai, it didn’t take the Germans long to make the link between her and Léonie Vanhoutte, although both women denied knowing each other. Louise was sentenced to death and Léonie received 15 years’ hard labour.

In a letter to the Carmelite nuns, she wrote: “I accept being condemned with courage. When I had my operation, I faced death with calm and without fear and today I add joy and pride to those feelings because I have refused to denounce anyone at all and I hope that those I have saved with my silence will appreciate it.”

Read more: France votes to rehabilitate memory of French soldiers shot for desertion in World War One

Life with hard labour

By this time, however, she was famous for her exploits, and following the international outrage at the executions of Edith Cavell and Gabrielle Petit, her sentence was commuted to life with hard labour.

She and Léonie were transferred to prison in Cologne. She refused to cooperate with her jailors, however, refusing to speak to them or do any work to help the German war effort.

Death in prison

She was flung into solitary confinement in a damp basement accused of inciting mutiny. Her health declined drastically and three years later, after the commander of the prison, Herr Dürr, ordered medical treatment to be withheld, she died in September 1918.

She was initially buried in Germany, but in 1920 her remains were transferred to France, and she was re-interred in the family crypt at Saint-Amand-les-Eaux.

Posthumously, she received the Cross of a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur, the Croix de Guerre 1914-1918, the Military Medal from the UK, and an OBE.

Léonie was freed from prison a few months later. Kate Quinn, author of the novel The Alice Network says that Louise was an extraordinary character. “She had a very vivid personality, but coming from a comfortably-off family who fell on hard times, she had to make her living as a governess. There wasn’t much other choice for women at that time.

There is no information available about any possible romantic relationships, so it’s impossible to tell whether marriage was out of the question because she never met the right man, or wasn’t financially a good catch.”

Kate notes that Louise was hired for her intellectual skills, but that as an upper servant she was overlooked, often ignored. “People who are overlooked hear everything. It was probably good training for a spy.”

She was successful in her career because she was stylish, effervescent and witty. But beneath the social graces, she was brave, determined and patriotic.

‘She understood what she was getting into’

Credits: Velvet - Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

“As soon as Lille was invaded, Louise was looking for ways to help. She knew full-well that running messages in and out of the occupied city was dangerous. She understood what she was getting into. Before she agreed to work for the British she consulted her mother and her priest. She looked at it in a very pragmatic way.”

When she set up her network, it became clear that she was a natural leader. People trusted her and wanted to follow her. She was intensely loyal to the women in her network, even, despite being a devout Catholic, arranging an abortion for a young woman who had been raped by a soldier.

After the war ended, Léonie and her husband Antoine Rédier wrote a book about Louise de Bettignies’ life called La Guerre des Femmes which was made into a film called Soeur d’Armes at the end of the 30s.

There is a statue dedicated to her memory in Lille.

Related links

Police seek witnesses after WW1 memorial gates stolen in north France

What is the history behind Paris’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier