-

French astronaut Sophie Adenot makes history as she blasts off on space station mission

Pupils in 4,500 schools set to copy her science experiments to compare results on Earth and in space

-

Films and shows to watch in February to improve your French

From understanding l’accent du midi to scenarios that have divided critics

-

Films and series to watch in January 2026 to improve your French

France is a hub of talent when it comes to film and TV, and watching in French can greatly improve your language skills

The French couple who loved, lived and died studying volcanoes

When scientists Katia and Maurice Krafft died on an erupting volcano they left a legacy of research that saves lives today

The volcanologists Katia and Maurice Krafft were ground-breaking scientists and explorers in the same mould as Jacques Cousteau.

Both from Alsace, Katia was born in 1942, and Maurice in 1946. They died on Mount Unzen in Japan, in a pyroclastic flow from an erupting volcano containing gases and volcanic matter. These flows can reach temperatures of up to 1,000°C and speeds of 700kph. Forty-one other people died in the same disaster.

‘Volcanoes were their children’

From childhood, both were fascinated by volcanoes. Katia nagged her parents for books about them and trips to see them, and at Strasbourg University she studied physics and geochemistry.

Maurice discovered volcanoes during a family trip to Naples when he was seven, and studied geology at university, also in Strasbourg. They met in 1966 at the University of Besançon and got married in 1970.

“They never had children,” says Fabrice Fillias, the Scientific Director at Vulcania (a science-themed amusement park. “Volcanoes were their children.”

He remembers as a boy attending a conference given by the pair, meeting Maurice Krafft and being inspired by their infectious enthusiasm for volcanoes.

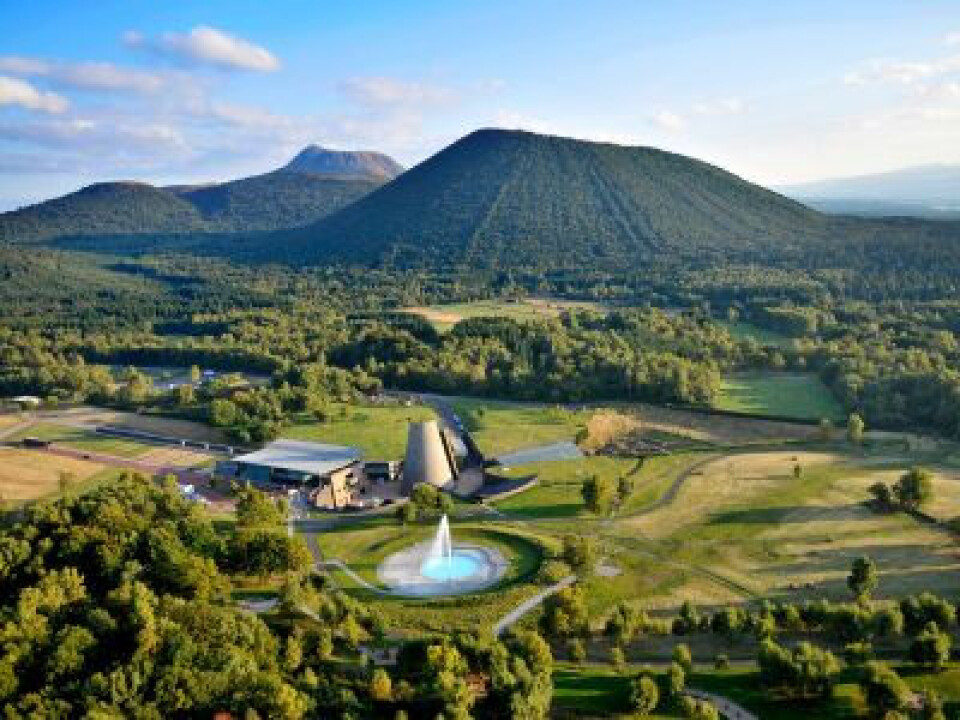

Photo: The Vulcania theme park educates people about volcanoes in a fun way

Their photos and videos funded their work

At that time, natural sciences were not as understood as they are now, and there was little funding for research. But the Kraffts were determined to study live volcanoes on site.

They scraped together the money to visit Stromboli in Italy, where they photographed the almost-continuous eruptions.

Back in France, people loved their photos and videos, and they realised that this was a way to fund their travels.

“Over the years they visited around 150 volcanoes; they were enormously experienced,” says Fabrice Fillias.

“It was rare for women to be eminent scientists at the time, but Katia Krafft won prizes for her work, and met Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (when he was Minister of the Economy and Finance) in 1972.”

Read more: ‘I tell women to be bold, no field is out of bounds’

‘A heady mix of science and adventure’

In 1968, they created the Centre de Volcanologie in Cernay (Alsace), where they collaborated with other scientific organisations including the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior (IAVCEI), the Smithsonian Institute, and the US Geological Survey. They had their first book published in 1971.

They went on to publish another 20 books, produce six full-length documentary films, and make countless television appearances, becoming known as the ‘Volcano Devils’.

As soon as a volcano began to erupt, the scientists would rush there, and as their fame grew, the Kraffts were invited all over the world.

“At the beginning it was a heady mixture of science and adventure. Volcanoes are exciting, and they were making new discoveries all the time which they wanted to share with the public.”

Photo: Volcanologists Katia and Maurice Krafft were ground-breaking scientists and explorers; Credit: United States Geological Survey

They studied ways to detect warning signs of an eruption

Through the EU’s Connaissance du Monde scheme, they gave talks to around four million people.

Connaissance du Monde organises cinema screenings of documentaries about the world, each one attended by scientists who talk about the film and answer questions. Screenings are held all over France.

“Volcanoes are very beautiful as well as being an exciting expression of our living planet. Over time, however, Katia and Maurice realised that volcanoes could also claim numerous victims.

“Even volcanoes which have slept for decades can erupt, and they studied ways of recognising warning signs, like slight earth tremors.”

The Kraffts divided volcanoes into two types

Red volcanoes emit lots of red lava fountains and heat, from which it is possible to escape because this lava tends to flow at around 5-6kph.

Grey volcanoes are more explosive and emit a lot of smoke and noxious fumes, and can also throw enormous rocks into the air. The ash and smoke goes in all directions and falls very quickly. It is impossible to outrun the explosive matter ejected by a grey volcano.

It is possible to build walls and gullies around some volcanoes, to direct lava away from settlements, but the burning gases and scalding ash can travel hundreds of kilometres. Then, for months afterwards, it dissolves in the rain and can cause landslides.

“The couple became a bridge between scientists in labs and adventurers on the ground.

“They returned from their expeditions with extraordinary photos and videos, as well as samples of gases and volcanic ash, and they also explained all this new science to the public.”

Read more: British-French scientist receives French honour in New Year’s list

Colombian volcano tragedy was turning point

Katia’s studies of gases could be used to predict an eruption, and this became especially important after the Armero tragedy in 1985.

The Nevado del Ruiz volcano in Columbia erupted after lying dormant for 69 years. Despite repeated warnings by scientists during the previous two months that it could erupt, the population of Armero was not warned and not evacuated.

On the day of the eruption, various inadequate evacuation efforts were made, but many people were advised to stay indoors.

Meanwhile, pyroclastic flows from the volcano melted glaciers in their path, sending four massive mudflows down the mountainside at speeds of up to 50kph.

The sticky, boiling mud engulfed the town of Armero (population 29,000), killing more than 20,000 people.

A further 3,000 people perished in nearby towns. The Nevado del Ruiz volcano has erupted several times since then, and continues to threaten up to 500,000 people.

“When Katia and Maurice Krafft turned up to photograph the eruption, the devastation was horrifying. They fell into another world. A world where volcanic activity wasn’t beautiful, it just created victims and destruction.

“That was when they decided to help people in a concrete way. In 1991, they opened a scientific centre, La Maison de Volcan, in Piton de la Fournaise in La Réunion.

“They also conceived the idea of a theme park called Vulcania, to educate people about volcanoes in a fun way. The project to create the park took years. “

Maurice always designed it to attract people wanting a fun day out, and then educate them once they got here. Back then, that was a very new approach,” says Fabrice Fillias.

“Every single attraction is educational in one way or another!”

Film saved around 10,000 lives in Mount Pinatubo eruption

The Kraffts’ 1990 film Understanding Volcanic Hazards, made in collaboration with UNESCO and the Office of the UN Disaster Relief Fund, was presented at the Congress of Mayence and almost immediately put to good use.

In 1991, as Mount Pinatubo began to show signs of imminent eruption in the Philippines, their video was shown to officials all over the country. It convinced sceptics to evacuate the zone, which saved around 10,000 lives.

Their bodies were found side by side on Mount Unzen

During their careers the Kraffts took more than 300,000 photos, 300 hours of film, produced 20,000 texts on geology, plus numerous lithographs and articles. Much of this is now housed at the Natural History Museum in Paris, but some can also be seen at Vulcania.

That same year, they were documenting the eruption of Mount Unzen in Japan when they, and a fellow volcanologist, Harry Glicken, were overtaken by pyroclastic flows from the volcano.

When their bodies were found two days later, lying side by side near their car, they were unrecognisable. Harry Glicken’s body was found further away, suggesting that he had tried to escape. They were only identified by personal items such as Maurice’s watch.

Their ashes were placed in the Anyo-Ji sanctuary in Shimabara, from where they were subsequently repatriated to Katia’s family plot in France.

Couple’s legacy lives on

Sadly, the pair died before the Vulcania project could be finished. Eventually it was taken over by the region of Auvergne, and Vulcania finally opened in 2002.

The Krafft Medal is awarded every four years by the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior to a person who has contributed to the service of people affected by volcanic activity.

The Centre for the Study of Active Volcanoes at the University of Hawaii has also established a fund in their memory, which helps educate people at high risk about volcanic hazards.

Films about their lives include Into the Inferno (2016) by Werner Herzog, The Fire Within: A Requiem for Katia and Maurice Krafft (2022), and Fire of Love (2023).

Related articles

Jacques-Yves Cousteau - undersea explorer, filmmaker and so much more

Simone Veil: a force for good, for women, for France, for all

Marguerite Durand: the force of France’s first feminist journalist