-

Five iconic French dishes from different regions

Explore the rich culinary heritage of France with these traditional dishes, from cassoulet in Occitanie to cari poule in La Réunion, showcasing the country's geographic and cultural diversity

-

Why does eastern France celebrate Saint-Nicolas on December 6?

Father Christmas may be known for his present delivery on December 24, but in the east of France, another bearded figure bearing gifts is celebrated much earlier in the month

-

5 French films and TV series to watch in December

From comforting comedies to powerful documentaries, there is something for everyone this winter

Straight to the (needle) point in Alençon, France

We unpick the history of the Queen of Lace and Lace of Queens in Alençon

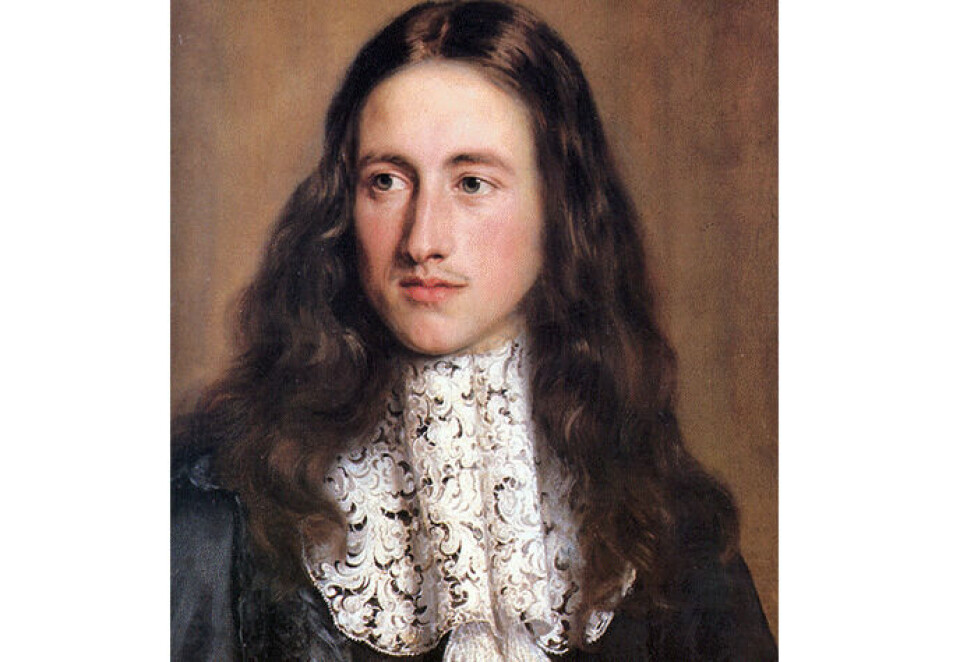

While on show at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in the Crystal Palace, London, Alençon lace earned a moniker that would stick: Reine des dentelles or Queen of Lace.

And for good reason.

The type of lace made in Alençon since the seventeenth century was more intricate, more labour-intensive to make, and as a result, more expensive than any other kind of hand-made lace.

But what makes it so special, and why did this exquisite fabric develop in a small town in Normandy?

Lace consists of two parts—a mesh, or réseau in French, and a pattern.

‘Point lace’ (made with a needle rather than bobbins) was developed by the Venetians as early as the sixteenth century, and the court of France was one of its most enthusiastic importers and consumers.

In 1577, for example, the king wore 4,000 yards of pure gold lace for an official event.

The centres of production at this time were Flanders and Italy, and vast sums of money flowed from France to import it.

The French monarchy was powerless to prevent French money being spent on lace in other domains.

So Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s minister of finance, decided to train up French craftspeople so that the production of lace, and the money to pay for it, would stay in France.

A declaration of 1665 ordered that lace would thereafter be made in France, and forbidding its import.

Devious smuggling

However, despite Colbert’s best intentions, foreign lace continued to find its way into France, sometimes in the most incredible and outlandish ways.

A lady called Eliza A. Youmans, writing about the history of lace in The Popular Science Monthly of 1875-76, describes how French smugglers would take a dog to the other side of the border with Flanders, leave it to half starve there, later returning to wrap lace around its diminished body.

They would then conceal the lace by sewing the skin of a larger dog over it.

The dog would later be released, running home, across the border, to find its owner and a proper meal, where it would be relieved of its precious cargo.

Meanwhile, on the right side of the law, in 1675, Colbert organised for 30 Venetian lacemakers to settle in Alençon.

These skilled individuals taught local needlewomen the point de Venise, and by the end of the century the locals had not only mastered the Italian craft, but made it their own with a variety of new stitches.

Alençon lace soon became the cream of the crop, surpassing other centres of needlepoint production such as Argentan.

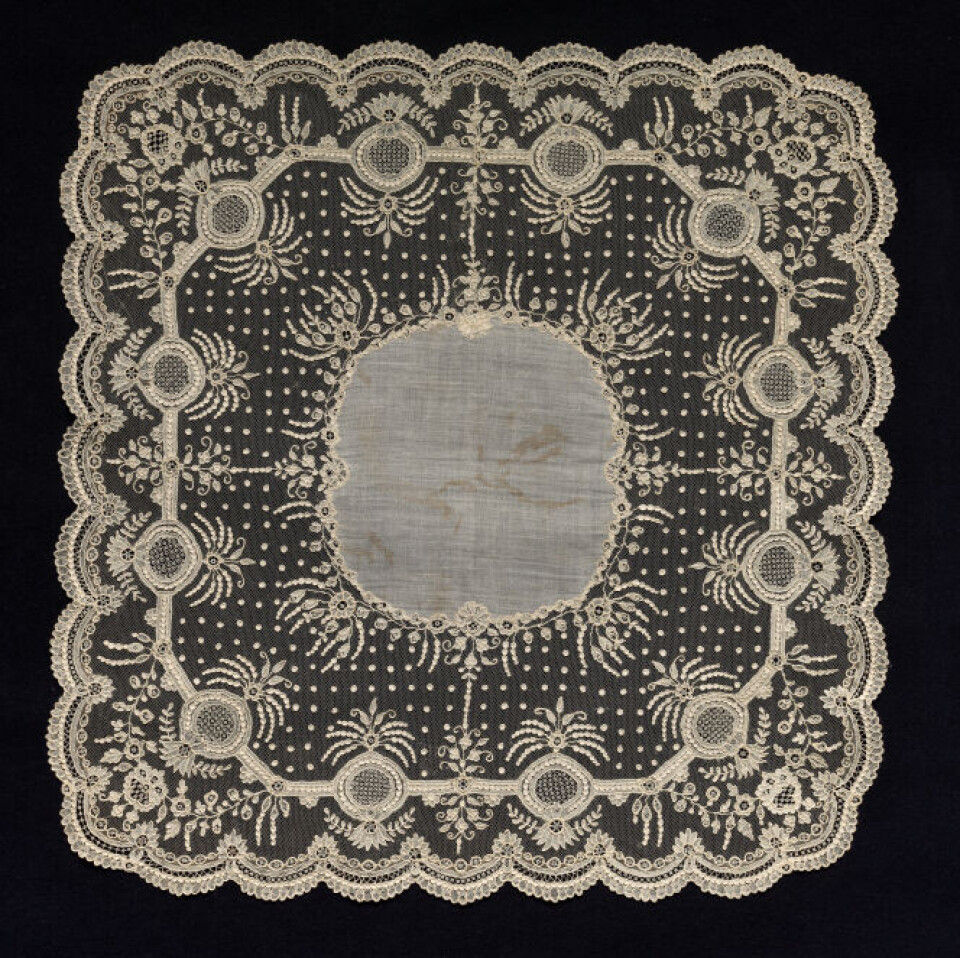

Point d’Alençon lace is made entirely by hand with a fine needle in small pieces joined together by invisible seams.

Alençon lace is identified by its delicate mesh ground and intricate designs surrounded by a raised rim called a cordonnet, and decorated with minuscule loops.

To ensure the uniformity of the loops, the thread was worked over the tip of a horse hair.

One of the final stages involves polishing the filling stitches with a lobster claw.

Negative association with the monarchy

The lace industry faltered during the Revolution due to its associations with the monarchy.

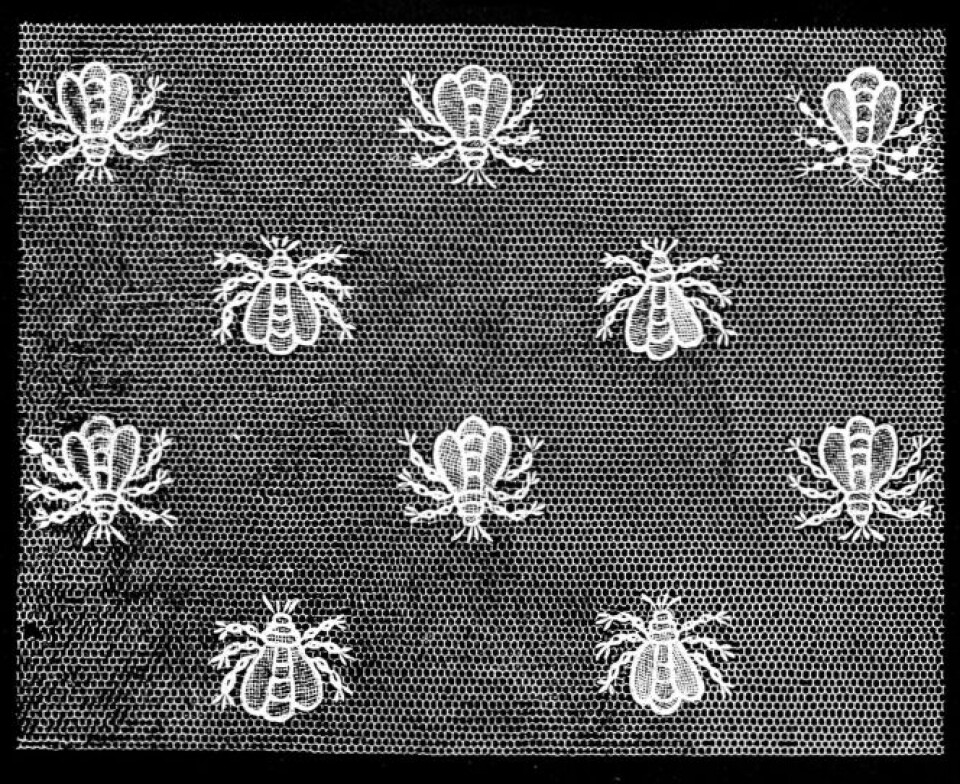

Napoleon I revived its production with a one-off commission of über-fancy bed linen to mark his marriage to the new empress, Marie-Louise, in 1810.

Each element was worked in Alençon lace and featured the arms of the empire surrounded by bees.

Alençon’s luxury fabric had another boost when in 1853 Napoleon III presented to his new wife, Eugénie, a piece of lace which had taken 36 women 18 months to finish, and cost 22,000 francs.

In 1856, the emperor ordered Alençon lace for the curtains of the imperial infant’s cradle, a christening robe, dozens of baby dresses, and to trim the aprons of the imperial nurses.

Up until the nineteenth century, artisans mastered one part of the lace-making process, but nowadays Alençon’s lace makers must master every single stage.

Because of its unique fabrication and preciousness, Alençon lace was added in 2010 to Unesco’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list.

Labour intensive

It takes between seven and 15 hours to make a postage-stamp-size piece of lace, and no machine can reproduce any stage of the work.

Apprentices take between seven and ten years to learn the technique at the Atelier conservatoire national de Dentelle et de broderie from the six ‘masters’.

And while a piece of genuine Alençon lace might be beyond most people’s budgets, everyone is free to admire contemporary and historical examples of these works of art at Alençon’s Musée des Beaux-arts et de la Dentelle.

Related articles

French art: Making an impression in the Hérault

Five French civil wars - from Charlemagne to the Paris Commune