-

Further sightings of processionary caterpillars in France prompt action from local authorities

Caterpillars have arrived early after mild winter

-

From Oregon to Brittany: primrose nursery in France celebrates 90th anniversary

Barnhaven Primroses traces its history back to 1930s America

-

Rugby vocabulary to know if watching the Six Nations in France

From un tampon to une cathédrale, understand the meaning of key French rugby terms

Diary of a birdwatcher in France: The Egyptian vulture

Jonathan Kemp explains how he was witness to some extraordinary behaviour by the smallest of the four vulture species found in Europe

We have recently lived through an event here in the Aude (Occitanie) that, for me, literally caught the feelings expressed in Emily Dickinson’s wonderful poem, ‘Hope Is The Thing With Feathers’.

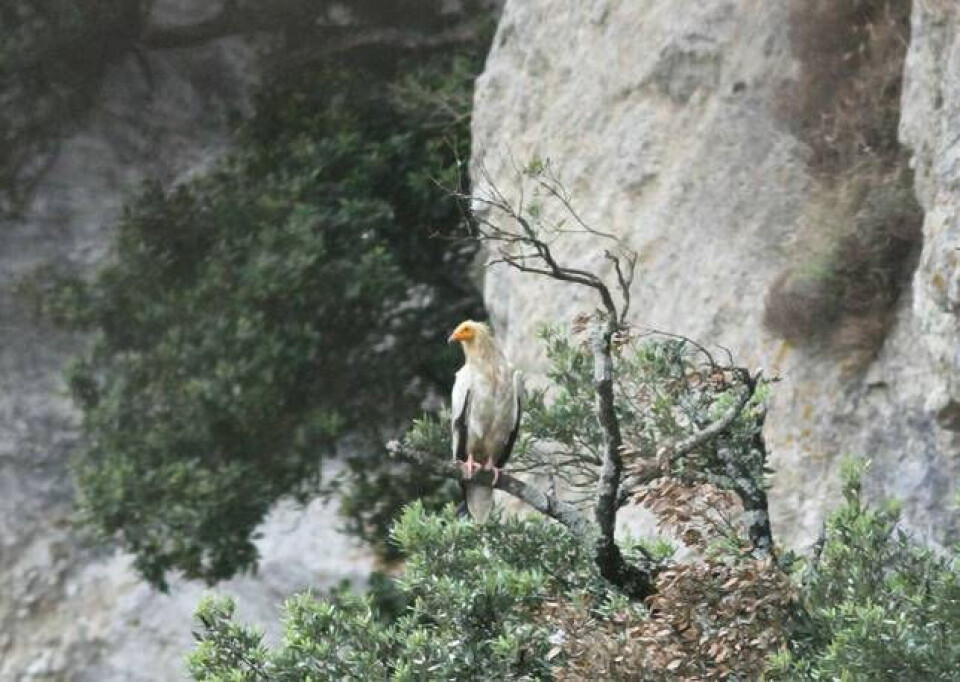

Late in the nesting season for one of our valued species, the Egyptian vulture (le vautour percnoptère), we discovered that a pair had chosen the most unsuitable nesting site. They had moved from a fairly secluded cliff face to position themselves within 140 metres of a busy main road, with a lay-by opposite and a disused railway line just below.

Not ideal for this rare and endangered species that has been the target of the EU LIFE programme (L'instrument financier pour l'environnement), which, in France has been successful, leading to a steady increase in the species over the last 20 years.

We in the Aude are proud to have up to six pairs nesting.

During the stage of building nests, layings eggs, brooding and up to hatching, the birds are easily disturbed and will abandon their nest if feeling threatened.

So, it was with care that we chose a remote observation site on an opposite hillside and watched the progress, even limiting our visits to occasional short stays. The last thing we wanted was to attract attention to the site, and draw too many people to watch.

Egyptian vultures practise asynchronous hatching, so there can be a difference of age between two chicks. This must not be too great, otherwise the demanding beak of the first born can lead to starvation for the second.

However both were seen to have hatched by June 17 and were being fed and growing.

Two chicks are quite common for Egyptians, it is quite possible that experienced, hardworking parents can raise both to fledging. Both share the feeding duties, the diet being varied, with carrion, insects and dung and some vegetable matter being eaten.

A major source of food here in Aude are the 23 farmers’ feeding stations, where the small Egyptians visit, staying on the periphery of the scrum of the other, larger vultures, and seeking scraps and leftovers.

After about 70 days, the elder chick was flying and started to explore the area in the company of one of its parents, but the smaller one, even though feeding well, made no attempt to fledge.

Normally around the end of the first week of September the two adults leave together for West Africa or Spain, having raised their chick(s) to flight and a certain degree of independence, building up their reserves to last them a few days.

Faced with this, the chicks also leave a day or so after. Their instinct will lead them to fly South, where they congregate in large groups and learn from each other where food sources are.

The mother left on schedule, and the more mature chick also disappeared. However, this is where things took an extraordinary turn.

What surprised us is that the male stayed behind, and continued to supply the single chick with food for another two weeks, which is the first time this break from the normal pattern has been witnessed.

He was able to make the judgement that this chick was not ready to fledge, and so broke the bond with his partner. Eventually he too was last seen on Tuesday, September 22, and disappeared.

The remaining chick continued to survive on scraps in the nest, and was seen exercising its wings, which is necessary to build up the muscles prior to flight.

However, each morning it was still there, somewhat active, sunning itself but often choosing to lie at the back of the nest. Both the site, low in a valley, and weather, without strong winds, were not ideal for a first flight.

A decision was made to send a climber down into the nest with supplementary food. I watched from the other side of the valley to judge the best moment so that it would not jump out in fear and fall below into the woods, or worse, make it to the road.

After a while it retreated to the back, I telephoned and the climber abseiled down. All went well, and we were pleased to see it eating. It was good that it ate as much as it could, as the local ravens were going into the nest and stealing the food.

Then, early one morning whilst stretching to reach some scraps at the front of the nest, he slipped and half-fell, half-flew. Two of us made our way to the woods where it should have been, but even with the help of two dogs were not able to find the bird.

After three hours scrambling about in the forest we abandoned the search. Happily someone else came in the afternoon to continue, armed with a recording of an adult Egyptian call on her phone, but after a fruitless hour sat down to rest.

It was at that moment she saw a strange, huddled shape, sitting out in the open. It was the chick! Walking towards it, it made no real attempt to fly away, so she was able to pick it up, tuck it under her arm, and walk back to the car, with only a couple of pecks on the way for her trouble.

It spent a night in a cage back at the offices of the local branch of the Ligue pour la protection des oiseaux. There, it was checked for growth and condition, and the decision was made, as it was under-developed, to transfer it to a specialist care centre where it would spend the winter in an aviary before being released in the area by us next March, when the others arrive back from migration.

Veterinary analysis has detected a certain level of lead in its blood which can lead to slow development.

So, against all the odds, a bird that I am calling ‘Hope, the thing with feathers’, with a mixture of luck, tenacity and avian intelligence, has survived to fly free again one day.

Jonathan Kemp moved to France in 1989 and lives in the department of Aude. He has been volunteering with the French nature association the Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux (LPO) for the past 20 years, working on a variety of different projects.

If you have a question about birds in France that you would like to ask Jonathan, you can email us at news@connexionfrance.com

Related stories:

Aude vulture watch station: What time of day is good to visit?