-

French MPs back plan to ban under-15s from social media

The bill also outlines rules for lycées

-

France’s end-of-life law under debate as conditions examined

The text centres on the definition of and access to ‘medical assistance in dying’

-

The five other capitals of France before Paris

Several other cities have held the honour for various reasons

How and why were France’s departments created?

It is well known today that the country is divided into 101 areas called départements . However, it was not always this way and their history dates back to the French Revolution

During the 18th century terms such as ‘assemblées’, ‘provinces’ and ‘municipalités’ were used to describe various areas of France.

They were mentioned in numerous works published by a range of French politicians, philosophers and economists, who each suggested some form of governing body within areas of divided land.

Provinces known as a pays d’états (an assembly formed of the three orders – the clergé, noblesse and tiers état) existed and the separation of land to collect taxes was a given.

Even King Louis XVI (1754-1793), apparently had plans to go down the route of provinces under his rule.

“France as a state had grown over the centuries by process of accretion, adding territories and allowing them specific privileges as provinces. Some provinces were very large, for example Brittany in the west, Languedoc in the south – but others were very small. It was all higgledy-piggledy,” explained Professor Colin Jones, CBE, Emeritus Professor of Cultural History, who specialises in French History and specifically the French Revolution.

Read more: 8 ways to appreciate French heritage (and for free) this weekend

But it was during the French Revolution (May 5, 1789 – November 9, 1799) that départements as we know them became a reality.

It was a time of social and economic change that highlighted the desire for simplification in France and, more importantly, the need for equality and unity. For the first time since 1614, King Louis XVI summoned the États Généraux to Versailles on May 5 1789 in an attempt to raise funds through taxes and solve the looming deficit.

But the tiers état had had enough. They were determined to change the current regime, perhaps surprisingly supported by a number of the clergé and noblesse.

“A nobleman, for example, proposed the abolition of France’s feudal regime. Many liberal nobles served on government committees.”

On June 17 the tiers état – with their fellow allies – declared themselves the Assemblée nationale and three days later, they made the Serment du Jeu de paume.

During a séance royale on June 23, King Louis XVI had grand plans to win the people back, including one that would establish provincial estates.

But it was too little, too late.

“One of the members of the national assembly, Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne (1743-1793) said, ‘History is not our code’. They wanted a constitutional system based on reason rather than precedent.”

The Assemblée nationale was successful in its mission.

It abolished current privileges and feudalism and created the Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen.

“The revolutionaries sought to make a blank slate of the past, ending all provincial privileges and aiming for a more uniform and homogeneous system of administration.”

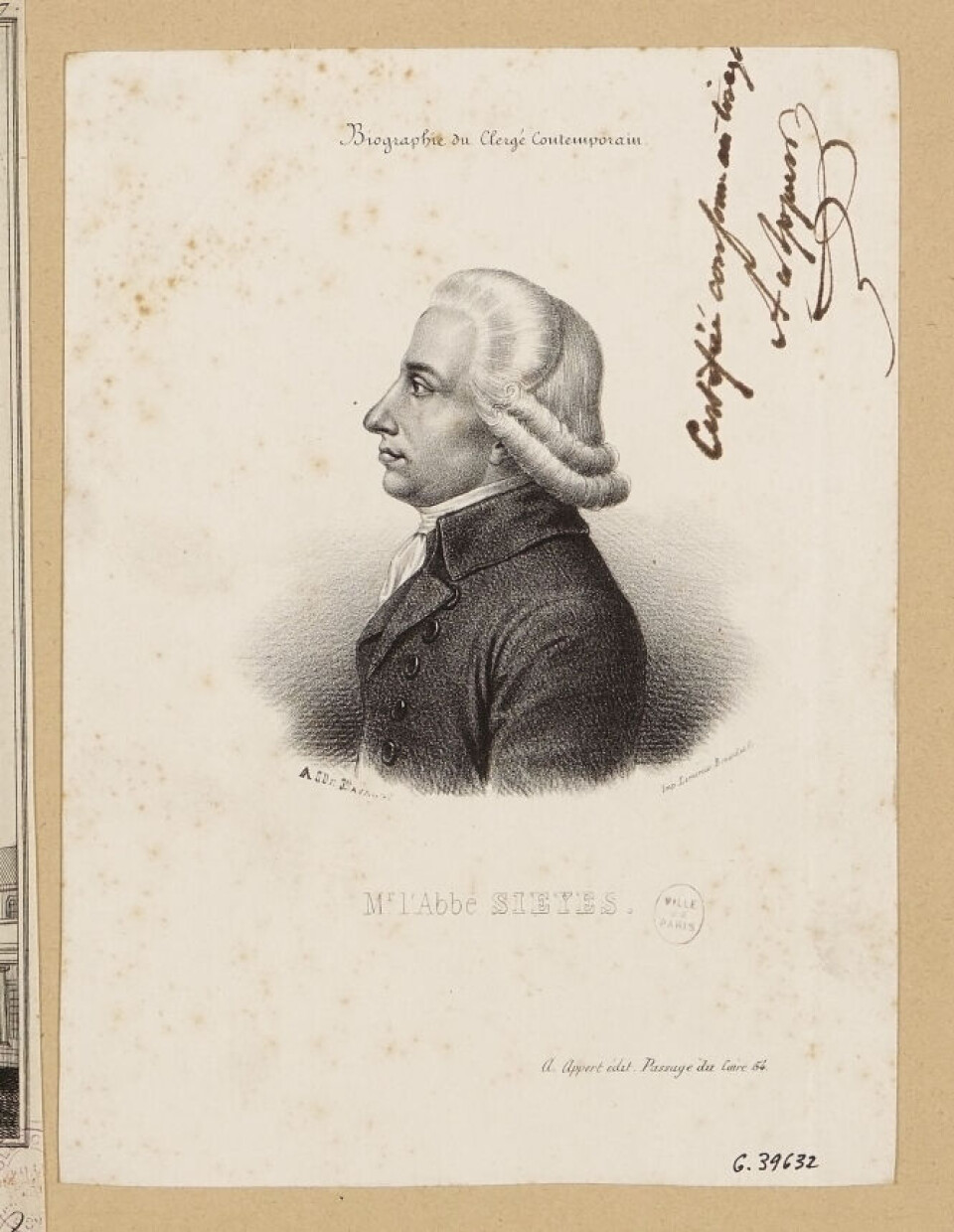

On September 7, Clergyman and author of ‘Qu’est-ce que le tiers état?’ Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès or Abbé Sieyès (1748-1836) suggested that the Assemblée nationale appoint a committee in charge of the administrative reorganisation in France.

His desire was that: “France may form a single whole, subject uniformly, in all its parts, to a common legislation and administration.” Six days later, a group of eight individuals, including Jacques Guillaume Thouret (1746-1794) and Abbé Sièyes, began establishing the administrative assemblies and the foundations for fair representation.

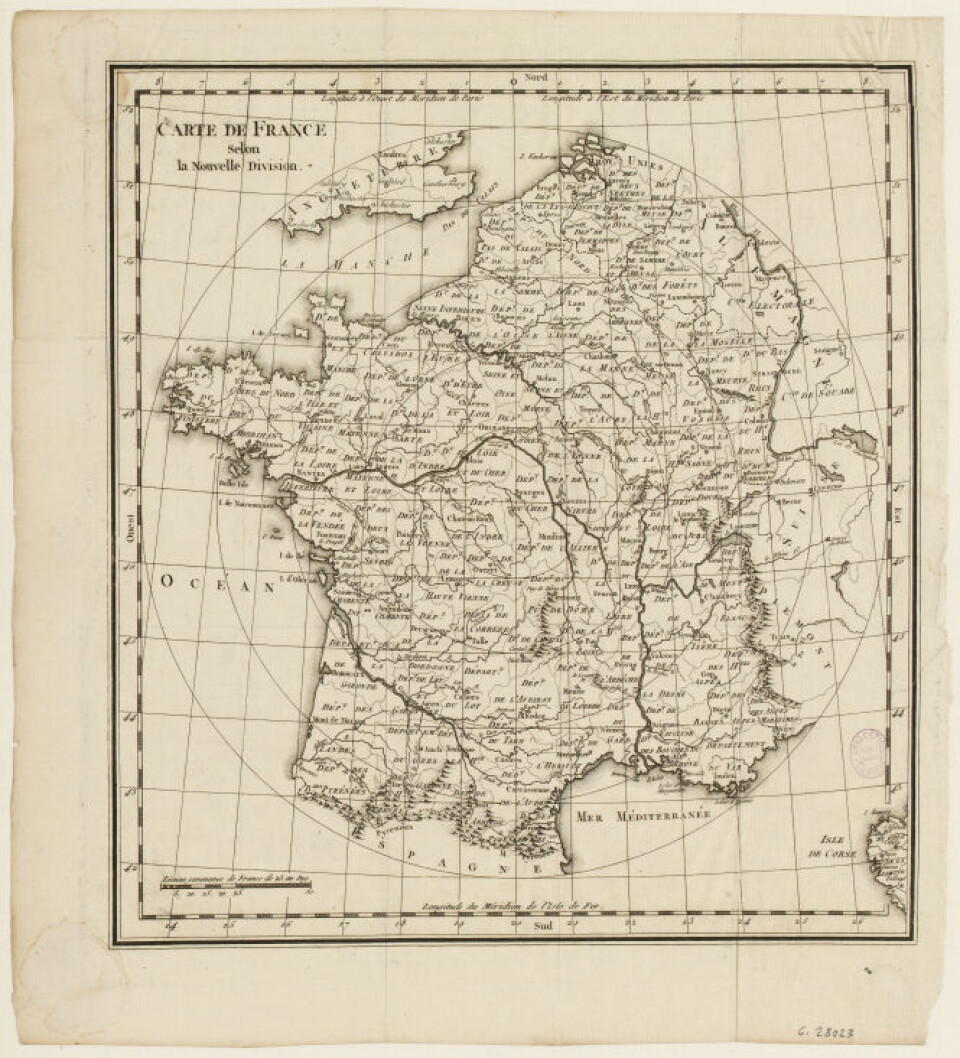

Based on the map by cartographer Mathias Robert de Hesseln (1732-ap. 1780) “Carte de France par quadrillage”, the country was divided into 81 départements, approximately 70 kilometres on each side, with each subdivision made of nine districts.

Read more: A brief history of French time and ‘timekeepers’

“There was some thought that they should simply draw straight lines across France to produce a kind of checker-board effect, but in the end they decided to go more with a system that allowed natural phenomena to guide the drawing of frontiers.

“Thus, rivers or other natural features were used in particular. They also, without always acknowledging it, sometimes used old provincial boundaries.”

In February 1790, the number of départements was finalised by decree, with their boundaries and administrative centres established.

“The result of the committee work involved was a collection of 83 departments, that were roughly similar in size and whose administrative capital was roughly a day’s ride from the furthest departmental boundary.

“They also decided that the names of each department would absolutely not be historic in any way but should evoke a natural feature of the department involved. These could be rivers (Seine-et-Marne) or mountains (Hautes-Alpes) or other such feature (Landes).”

Specific items confirmed the division of each département into three to nine districts and setting the number of seats in the Assemblée nationale.

More importantly, it ensured the right to vote, and each département would have an administration de département, with a conseil général and a directoire, as well as 36 members, elected for four years (renewable every two).

It was the end of the Ancien Régime.

Over the next few years, wars increased the départements to 113 and Napoléon Bonaparte’s (1769-1821) expeditions increased France’s empire to 130 départements (134 with the French départements in Spain).

Read more: This month in history: Peace talks, people’s Louvre, mademoiselle ends

In the early 19th century, the départements were centralised and divided into districts and communes.

Napoléon specifically created the role of the préfet to be the official representative of the département, with the purpose of liaising with the State.

The position carried a lot of weight since he personally selected them and apparently referred to them as ‘empereurs au petit pied’. He also chose the members of the conseil général.

“The prefects were against the spirit of the creation of the departments, for the idea in 1790 that the key administrators in each department should be elected. The democratic nature of the departments was important,” said Professor Jones.

“What Napoléon did was replace an elected official by a government nominee. This made the departments very much more under a control of central government than was the original idea.”

The role of the préfet continued to develop over the years, with a focus on economic and social matters. In March 1852 a decree bestowed more power upon them, with a memorable motto in the preamble: “We can govern from afar, but... we administer well only from near.”

In 1871, départements became collectivités territoriales, separating their administrative organisations from the State.

The number of départements continued to fluctuate for varying reasons, such as the division of land after the First World War (July 1914-November 1918) and the reorganisation of the Paris region in 1964.

During that time a law had been put in place to ensure the election process of a conseil général was by universal suffrage.

The beginning of the 1980’s saw the start of a large decentralisation process, of which ‘loi dite 4D’ for ‘décentralisation, différenciation, déconcentration et décomplexification’ is currently taking place under President Emmanuel Macron.

The law of March 2, 1982 was an essential step in providing the communes, départements and the regions more freedom and authority.

There is also more encouragement to collaborate with one another, working together to develop financial and human resources.

Today, there are 101 départements in France that have representatives elected with specific areas of responsibilities close to the inhabitants.

It has been over 230 years since Abbé Sieyès expressed his desires for France. While it is no doubt a fluid situation, hopefully it is a step in the right direction that he might approve of.

Professor Colin Jones CBE is the author of several books including ‘The Fall of Robespierre. 24 Hours in Revolutionary Paris’.

Related stories:

Marseille: The cultural melting pot of France’s south