-

Loire vineyard invites Taylor Swift to visit after documentary cameo

Disney+ documentary puts family vineyard in the international spotlight

-

39 bombs wash up on Gironde beach following World War Two bunker collapse

Shells were defused by experts but prefects warn others may remain

-

French airports request EES rollout suspension this summer

Risk of congestion feared if April full deployment of system for all eligible passengers takes place

French Minister: Detection of Covid Congo strain shows tracking works

Twelve cases of a variant have been found in France, which the health minister says highlights France’s ‘very strong’ ability to track variants

France’s health minister has used an example of a Covid variant thought to have originated in the Republic of Congo as an example of the country’s ability to track mutations of the virus.

A small number of cases of the variant have been detected in France and in other European countries, such as Italy, Netherlands and Spain.

“France is one of the countries that performs the most virus sequencing [in the world],” Olivier Véran said in an interview with Ouest-France on Tuesday (November 16).

He said that some cases of the variant had been identified in Brittany and a few other cases in Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, with 12 cases in total reported in the country.

He said that he was not highlighting the variant’s presence to worry people, but rather to show that France was capable of tracking the virus’ mutations.

“There is nothing to indicate that this variant is particularly dangerous, but [I am mentioning it] to underline that our capacity to track down variants is very strong,” he said.

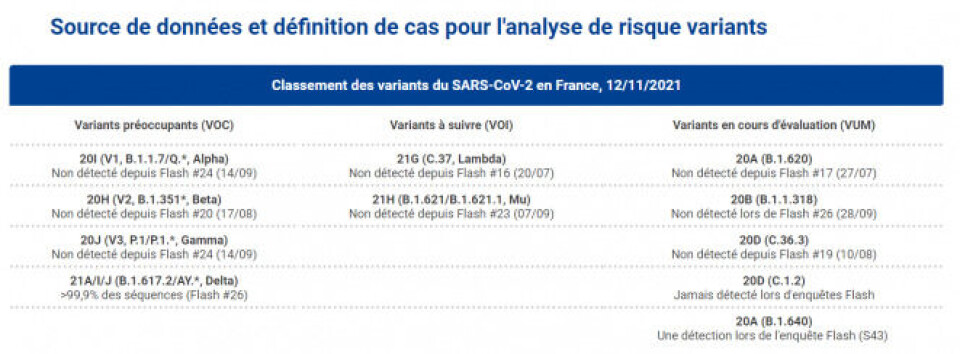

The variant, which has been denoted B.1.640, was added to France’s list of “variants under monitoring” on November 12.

France classifies variants in three ways: variants of concern, variants of interest, and variants under monitoring.

Variants of concern are the most problematic, and included on that list is the Delta variant, which is now by far the dominant variant in France. There are four other variants in the category of variants under monitoring aside from B.1.640, with these rarely or in one case never having been detected in France.

What is known about B.1.640?

The first known case of it dates back to September 28 in a patient in the Republic of Congo.

A total of 28 cases of it have been recorded worldwide. The Republic of Congo and other developing countries have much less sequencing capabilities in France, which could distort the picture of how many cases of the variant there are and where they are.

B.1.640 is also classified as a variant under monitoring by European and British health authorities.

Scientists have reported that it has a surprising genomic diversity, meaning that the variant has several diverging mutations, but they can all be classified under the variant of B.1.640.

This diversity suggests that the variant is not necessarily new, as it takes time for mutations in a variant to occur.

“One possibility is that this variant has been potentially circulating at low levels for some time, in Africa or elsewhere, in places where genome surveillance is lower,” Étienne Simon-Lorière, a virologist at the Pasteur Institute, told HuffPost.

He said that it is very difficult to know exactly where it came from or how it will spread.

"We are currently unable to say whether this variant will die out or develop," he said.

Florence Débarre, a scientist and researcher at France’s national research centre, the Centre national de la recherche scientifique, told HuffPost that it served as a reminder that other variants are circulating, despite the dominance of Delta.

“It was said that Delta had become hegemonic and that the next variant would be one of its descendants. This [B.1.640] is another very different branch, a lineage that seems to have lived its life off the radar,” she said.

“It is a reminder that several versions of coronavirus are circulating in many parts of the world where there is very little genomic surveillance and few vaccine doses have been administered.”

How is France tracking variants?

Health minister Mr Véran highlighted France’s ability to track variants through a technique called sequencing.

This is where a positive PCR test is processed (to identify RNA molecules) and then converted into DNA that can be read so scientists can see the complete genetic makeup of the virus.

This can then be compared to other samples and allows scientists to track how the virus is mutating.

You can read more about how France is using sequencing to track variants in our article here: How is France tracking spread of Indian variant of Covid-19?.

However, France’s sequencing capacities have not always been so developed. As recent as earlier this year the country was far behind the UK and US in its ability to track variants through this means.

Professor Karine Lacombe, head of the Infectious Diseases Department at Hôpital Saint-Antoine in Paris, admitted that English-speaking countries such as the UK and the US were better at sequencing than France, in an interview with BFMTV on May 16.

“We are not yet at the level of the UK or the US...but a lot of progress has been made,” she said.

In January 2021, France launched the EMER-GEN consortium, which is working to create a genomic surveillance system for SARS-CoV-2 infections throughout the country. The consortium has several partners, including Santé Publique France, and has increased sequencing capacity.

France is carrying out ‘flash’ surveys, where every two weeks thousands of tests around the country are sequenced. The results are then published a few weeks later.

The country is also using a technique called screening (criblage, in French).

All positive Covid-19 tests in France are subject to screening. This is where the tests are sent off and analysed for specific mutations - so it does not give a picture of the entire genetic makeup of the sample, as sequencing does.

Related stories:

Covid-19: Study shows the current situation of variants in France