-

Bikers tag dangerous French roads to shame authorities

Operation carried out for a number of years by local groups of the Fédération française des motards en colère

-

Transavia to replace Air France for Nice-Orly flights

Up to eight return journeys a day to be offered by the budget carrier

-

Is this the end of free mountain rescue in France?

A new report says that charging for services is ‘legitimate and necessary’

Macron and Le Pen’s election rematch: A lot has changed since 2017

Polls and experts suggest that the race between the candidates will be far closer, after an embattled five-year term for Macron and the ‘dédiabolisation’ of Le Pen

President Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen will face each other in the second round of the presidential election on April 24, just as they did in 2017 – but the political situation five years on is very different.

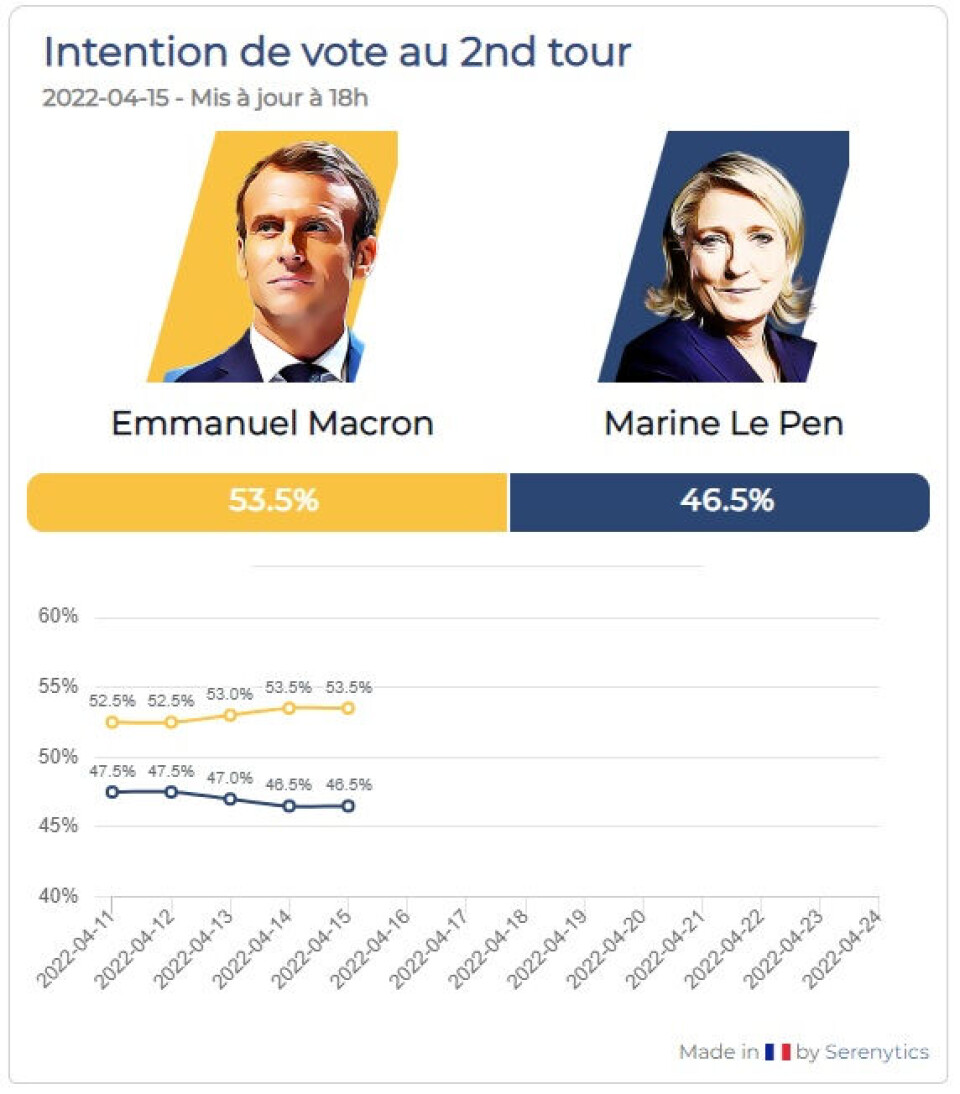

In 2017, Mr Macron won with 66.10% of the vote. This time, survey figures from April 15, from pollster Ifop put them closer, with Ifop showing Mr Macron as favourite on 53.5% versus Ms Le Pen’s 46.5%.

We asked Stéphane Rozès, a political science lecturer at Sciences Po, and Delphine Marion-Boulle, a journalist and author, what has changed between the two elections.

Macron needs to defend his five-year term

One key point is that voters can now look at what Mr Macron has achieved as president.

“President Macron’s term has been blighted by his inability to get France back on track, as he promised to do as a candidate in 2017. This has in turn accentuated French disillusionment in politics,” said Mr Rozès.

He said the public’s perspective of Mr Macron has changed as in the 2017 election he was seen as a candidate challenging the natural order of French politics by campaigning – for the first time – under the political banner of a new party, La République en marche.

He said that when French people go to vote, they should consider the accomplishments of his full five-year term.

This is an argument that Mr Macron’s rivals, Ms Le Pen and the left-wing Jean-Luc Mélenchon (from La France Insoumise, who was eliminated in the first-round of the election but received 7.7 million votes) have both made.

The millions who voted for Mr Mélenchon are now seen as key voters, with both candidates actively trying to woo them. In 2017, Mr Macron was seen as centrist but has veered to the right during his presidency.

Read more: 'Macron or Le Pen: It's like choosing between the plague or cholera'

Read more: French election: The chase is on for Mélenchon’s 7.7 million voters

A poll published on the evening of the first-round of voting showed that 23% of Mr Mélenchon’s voters said they intended to back Ms Le Pen in the second round, almost triple the 8% who did so in 2017.

Macron’s term in office has also eroded the notion of “front républicain”, a French political concept that describes attempts by opposition parties to join together in the second round of elections to block extremist parties from reaching office, said Mr Rozès.

Mr Macron’s presidential stance has also been weakened by the barrage of criticism during the gilets jaunes protests, critics of his handling of the coronavirus pandemic and “several regrettable quotes”, all of which are playing a part in making people hesitate to vote for him in 2022, said Mr Rozès.

Read more: ‘Piss off the unvaccinated’: Not first time Macron’s words cause stir

“The abstention rate, blank votes and spoilt votes will be the key of the second round,” said Mr Rozès, referring to the transfer of votes from Mélenchon’s supporters.

Mr Mélenchon himself has not advocated voting for Macron to his supporters – he has only told them not to vote Le Pen.

Le Pen appears more like a ‘normal candidate’

Ms Le Pen’s second successive qualification for the run-off and the 8.1 million votes (23.1%) she received during the first round is the result of a ten-year-long political tactic to make her far-right party – Rassemblement National – appear more moderate, Ms Marion-Boulle said.

This tactic has been dubbed “dédiabolisation” (de-demonisation).

Her more moderate image ahead of the first round was also formed in part by the presence of the more extreme far-right candidate, Éric Zemmour.

“Mr Zemmour’s ideas on immigration have helped Ms Le Pen’s ideas seem more acceptable simply because they are, in comparison to Mr Zemmour,” said Ms Marion-Boulle, author of ‘Au nom de la race: Bienvenue chez les suprémacistes blancs’, a book about white supremacy in France.

Read more: Former French PM says Le Pen can win, Zemmour makes her look moderate

She said Ms Le Pen’s campaign was helped by Mr Zemmour speaking about the “great replacement,” a conspiracy theory that claims white people are being replaced by ethnic minorities.

Ms Le Pen, on the other hand, has distanced herself from this theory, making her appear as the more moderate of the two candidates.

Read more: ‘Why the ‘great replacement’ theory does not make sense in France’

Her acceptability among voters is reinforced by her social media presence, where she is often associated with cats after having been found to be running a secret Instagram account dedicated to her pets.

This resulted in more voter support from both sides of the political spectrum.

Several of her political adversaries have raised doubts about the reality of her "dédiabolisation" campaign. Many defenders of Mr Macron suggest she is not presenting her true views and, for example, she is still in favour of France leaving the European Union.

Read more: Le Pen praises Brexit; Macron and allies say she is hiding Frexit plan

However, Mr Rozès did not doubt the truthfulness of her ‘dédiabolisation’ when asked about it, saying Ms Le Pen differed from other far-right candidates such as Mr Zemmour on “ideological content.”

Ms Le Pen has focused much of her campaign on household spending power – the issue that tops polls into voter topics of concern – and has been more discreet about her more controversial policies on immigration and religion.

This worked well in the lead up to the first round of voting, but in the past week she has faced criticism for her more extreme policies, including her “French nationals first” plan, which aims to give French nationals priority for jobs, housing and social aid.

Read more: What is Le Pen’s ‘French nationals first’ policy and is it legal?

Related articles

What is Marine Le Pen’s position on the death penalty?

Macron - Le Pen: What do they each pledge to change if elected?