-

More French podcasts to test your language skills

Podcasts are one of the best free tools for consistently developing your listening comprehension

-

Rugby vocabulary to know if watching the Six Nations in France

From un tampon to une cathédrale, understand the meaning of key French rugby terms

-

Learning French: what does faire grise mine mean and when should it be used?

A phrase to use when someone is down in the dumps

Senate ban on inclusive language: French experts give pros and cons

The overwhelming majority of senators have voted to ban gender-inclusive writing in official documents. We spoke to experts on both sides of the debate

Almost three-quarters of senators have voted in favour of a bill to ban gender-inclusive writing from all areas where French is legally required “in order to protect the language”.

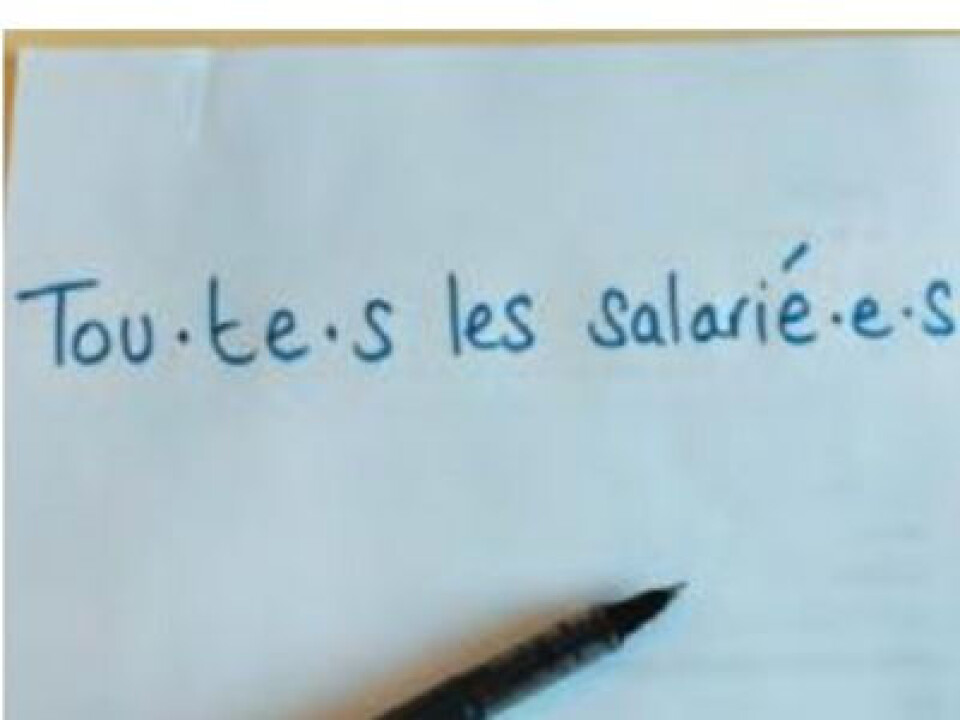

The legislation, if passed, would prevent a generic masculine being replaced by masculine and feminine forms. Examples in use include ami·e·s (friends) and artisan·e·s (craftspeople).

The ban would cover education as well as adverts, instruction leaflets, job offers and all official documents.

It would automatically nullify legal documents that contain it unless they also carry a translation into traditional French.

Read more: Senate votes to ban ‘inclusive language’ from official French texts

The bill must be approved by MPs, who are divided on the topic, to become law.

Senators say the language is a barrier for people with learning difficulties. The Ministry for Culture issued a ‘recommendation of wisdom’ about the bill.

Other countries with gendered language have also pushed back against this.

Berlin mayor Kai Wegner said he will not use it and the world’s oldest linguistic academy, Italy’s Accademia della Crusca, said the masculine plural was the “best way to represent all genders”.

We spoke to two experts on both sides of this debate.

Argument for inclusive language

The bill is proof that there is still a lot of work to be done to clarify the purpose of inclusive writing, said linguist Jana Rameh, a consultant at Mots-Clés, an agency that helps firms adopt inclusive writing.

“What it seeks to do is to build a language that is more egalitarian, that is more inclusive for everyone,” she said.

“It’s a way of moving towards greater equality between women and men.”

It has led to a rise in women applying for certain jobs, as well as an important shift in work culture, she said.

“You can’t use inclusive writing and have a gender pay gap or be sexist at a company,” she said.

For Ms Rameh, changing language to reflect a shifting society is fundamental.

“Any living language, by definition, has to move,” she said.

“Language evolves from the desire of its speakers to express certain needs that cannot be expressed using existing means.

“French is perceived as more fixed because there’s a certain institution responsible for regulating the evolution of the language.

“Historically, there have been a lot of debates about gender and inclusivity, and in fact before the 17th century each profession had its respective feminine form. It was with the establishment of the Académie française that we moved towards a language that was masculine.”

Read more: Debate over gender-inclusive terms in French reopens

She added: “Inclusive writing is a lever for working on gender equality.

“It’s not at all a question of undermining existing grammar. It’s about making a personal effort to use the means that are already present in our language.”

Ms Rameh dismisses claims by supporters of the ban that inclusive writing hinders reading and comprehension.

“The Catalan alphabet uses the mid-point [full stop] between two l’s, to say that it means something different. For people who speak Catalan, even those with dyslexia, it’s not a problem.

“The idea would be to teach this from an early age and help schoolchildren understand that, for example, the mid-point is just an abbreviation.

“In French, it’s hard to separate the grammatical gender from the neuter for human nouns. Inclusive writing allows a certain linguistic inventiveness.

“By using the median point, or employing words such as ‘iel’, non-binary people are better reflected in the French language, far more than when only the generic masculine is used.”

Photo: The mid-point [full stop] is included to represent both masculine and feminine rather than just using the masculine form to represent both; Credit: Scheenagh Harrington

Argument against inclusive language

Changing the French language runs the risk of distancing future generations from the country’s formidable literary past, warned Sophie Audugé, spokeswoman for SOS Education, a non-profit aiming to improve the education system.

“There’s a clear danger in cutting our younger generations off from history and making them believe that there’s a need in France to feminise the language to improve equality between men and women,” she said. “It’s not true.

“I think our younger generations need to learn from women’s struggles, whether it’s Colette or Simone Veil, to understand how a woman today takes her place in society: through education, through intellectual demands, through the battle of ideas with men, and through her ability to develop a way of thinking.

“It’s certainly not by lowering the level of education, by making cosmetic changes to language, that we will improve the status of women.

“On the contrary, today more young girls from the least privileged backgrounds don’t have access to education to escape from the situation.

“That’s where the battle lies.”

Read more: Should the French language be changed to be made less masculine?

When asked how it could help members of the LGBQT community feel more visible, Ms Audugé replied: “It is what you might call an identitarian essentialism. It’s strategic and political.

“The majority of people in these communities have no desire to be singled out for this part of their identity.

“Let’s be clear, there’s nothing more communitarian than telling someone ‘we’re going to make you visible’.”

Alongside the weight of intellectual history, she also cited a major report from SOS Education about the complications that inclusive writing, such as using the median point, could pose to blind and partially sighted people, as well as those with autism, dyslexia or dyspraxia.

None of which means French cannot evolve with a changing society, she said.

“We can be resolutely modern, while preserving the French language identity.

“The Académie française dictionary is a benchmark because, obviously, a national language takes a long time to develop. That is something that we have to recognise and respect.

“But there are institutions that don’t have to let themselves be carried away by fashions, and which must preserve what is most profound in a nation’s identity, which is its language.”

The rolling publication of the ninth edition of the Académie française dictionary, first published in 1694, is now up to the word spermatophytes and can be found online.

Related articles

Why France is more resistant than many countries to wokeism

President opens 'first-ever’ centre dedicated to French language

A French perspective on sexism to mark International Women’s Day