-

France’s Favourite Village 2026 shortlist announced

You can vote for your favourite until early March

-

Exploring Pont-Croix: officially named as France’s best tourism village

A Breton gem boasting strong cultural heritage, charming architecture and vibrant local life

-

The five other capitals of France before Paris

Several other cities have held the honour for various reasons

French architecture: Pont du Gard is country’s most visited roman site

It is the highest aqueduct built in the Roman Empire, and is situated just 20km from Avignon

France has one of the most important architectural structures dating back to antiquity – the Pont du Gard.

It is unique in its construction, as well as being the highest aqueduct to be built in the Roman Empire. Situated 20km from Avignon and 23km from Nîmes, it has been a Unesco World Heritage Site since 1985 and it is the most-visited Roman site in the country.

The Roman architectural marvel

The bridge was built by the Romans in around 50AD and was the centrepiece of an astonishing aqueduct which took running water to what is now Nîmes for around three centuries.

It fed the fountains installed in every street, the spas, gardens and private homes.

Nemausus, as Nîmes was called at the time, was one of the major Roman cities in France, with an estimated 20,000 inhabitants. It had all the characteristics of a modern town, with a forum and temple, but although water was available from wells and rainwater, it was not abundant, and the population was growing.

To give the city real status, it needed flowing fountains in its gardens and the ability to change the water frequently in its public baths.

There are no records of who came up with the idea of an aqueduct, nor of who financed it, and no one knows who the architects and engineers of this extraordinary structure were, but Pont du Gard guide Laurent Charrière says it is likely the experts came from Rome, where they already knew how to build aqueducts.

This one, however, posed new challenges.

“The nearest suitable spring was the source of the Eure River, at Uzès. The direct route between the towns is 23km, but there is a hill in the way, so the aqueduct had to be 50km long to get around it.

“The difference in height between the source and its destination is just 12m, so the gradient had to be very shallow.

“This meant that the only way to cross the valley of the river Gardon was by building a very tall bridge, 48m high, so as not to lose too much height.”

He says these constraints are why the bridge is unique: it is made up of three bridges, one on top of the other. The first has six arches, the second 11, and the top level, which carries the canal, 35.

“This was the design they came up with to make such a tall bridge solid. Not only did it have to be very high, it also had to resist the waters from the river, which can rise suddenly with enormous force in autumn and winter rains. Having three bridges made it very heavy, strong, and difficult to destroy. It is estimated it weighs 50,400 tonnes, the equivalent of five Eiffel Towers.”

Each level of bridge is narrower than the one below, to add to the construction’s solidity. The arches on the first and second levels are roughly the same size, though the arch spanning the river on the bottom layer is the largest at 24.5m, and one of the widest to be built by the Romans.

Fortunately, there was suitable stone nearby, dug from the Carrière de l’Estel, just 600m from the bridge.

“The stone is a soft, yellow, shelly limestone,” says Mr Charrière. “It is easy to cut and shape, but once in place, and compacted, it becomes resistant. It is a stone that is still used today for balustrades, staircases and terraces.”

Built with slave labour

It is estimated the bridge took five years to build and the whole aqueduct, from source to city, took 15 years.

Around 500 workers were taken on to build the Pont du Gard, and the same number again for the rest of the aqueduct.

Some were paid, but slaves were also used, not just for the manual labour but for skilled work such as shaping the stone.

First, the pillars on the bottom bridge were built, followed by the arch and then the top, and this process continued up each of the levels.

Wooden scaffolding was used, built by skilled carpenters. There were also cranes, powered by slaves walking within a treadwheel, which drove the hoisting and lowering device, capable of lifting huge blocks of stone.

It is thought the aqueduct worked until 500AD. However, it is likely it took water to Nemausus for only around 300 years, after which the city’s importance dwindled and, with it, its population.

Keeping the water flowing freely required a lot of maintenance work to clear the limestone deposits which built up. This was a physical job, no doubt carried out by teams employed by the city, and which would have come to an end with the decline of Nemausus.

The water which still ran through the aqueduct for the next 200 years was probably used by farmers for irrigation.

Transformation into a historic monument

By the Middle Ages, however, the structure was no longer in use and people pilfered stone from it for their own building projects.

Though the aqueduct was never designed as a road, people began using it to cross the river in about the 11th century. They hacked away stone from the pillars on the first level to make it wide enough to take a horse and cart.

“This, in fact, saved the Pont du Gard,” says Mr Charrière.

“A toll was charged for crossing the bridge, making it a valuable source of income. Otherwise, it might have been entirely dismantled over time for its stone.”

Much later, in 1743, a parallel bridge was built, which could take more traffic.

It was only in the 19th century that the intrinsic value of ancient monuments began to be appreciated.

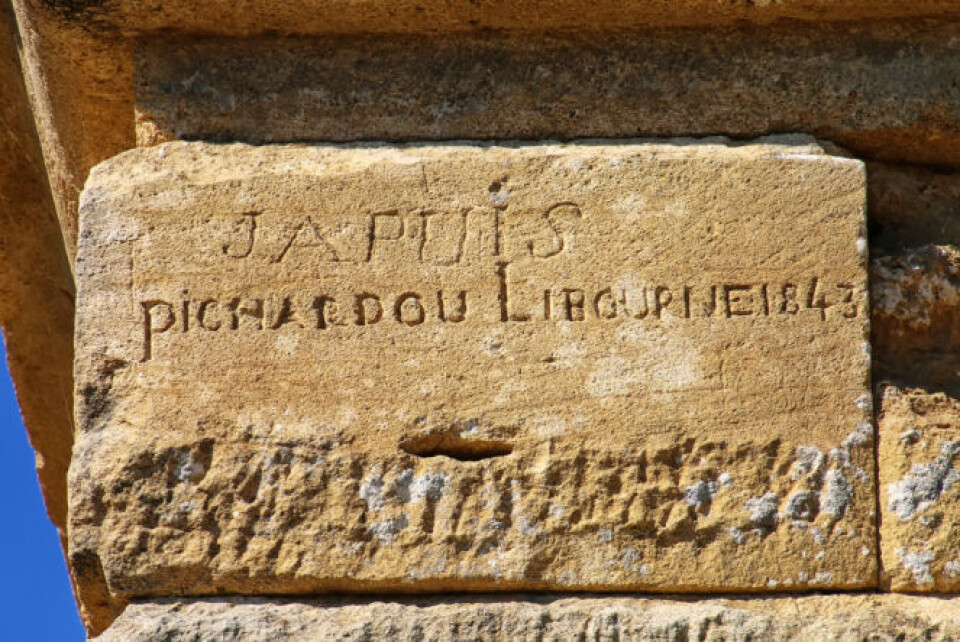

In 1840, Prosper Mérimée, the first inspector of historic monuments, listed the Pont du Gard as one of the most important structures in France, meaning its future was assured and the pillars were restored.

From the 20th century, the bridge started attracting thousands of tourists. The parallel bridge was closed to traffic and, in 2000, the site was revamped to better accommodate tourism, while preserving the bridge and the local environment.

There is now a museum showing how it was built, and it is also possible to book a guided tour along the canal at the top of the bridge.

The first small section is open to the sky but most is in a tunnel, as the waterway was covered along its whole length to protect it.

Mr Charrière says that while the Pont du Gard is inarguably beautiful, we must remember that it was not built simply to look good.

“The aim was to find the simplest and best way to make something that was to be useful. The modern-day analogy is a motorway bridge, which engineers and architects design to serve a purpose, using the most economic and practical methods.”

Related stories:

‘Village of cats’ in south of France inspired by an old legend

One tower per family in this noble medieval site in France

Château de la Mercerie: Folly of brothers who could not stop building